‘Let's Be Honest, Moms Are Never In the Photo’

The photographer Nancy Borowick takes on a taboo topic and puts mothers at the center.

In 2012, when Nancy Borowick’s mother, Laurel, was battling a second recurrence of breast cancer, Nancy’s father Howie—Laurel’s husband of 34 years—received his own devastating diagnosis: Stage 4 pancreatic cancer.

Nancy had been working as a photographer for several years by that point. She’d been documenting her mother’s illness as a way of connecting with her—shooting her as she battled the disease and came to terms with a new way of life. When Howie was diagnosed, he asked Nancy to do the same with him.

Howie died on December 7, 2013. On December 6, 2014—one day shy of one year later—Laurel died. In 2017, Nancy published “The Family Imprint” a monograph that chronicles the 364 days that her parents were in parallel treatment, in some cases literally side-by-side, for their respective cancers.

The book received immediate acclaim, winning Nancy dozens of awards and whisking her around the world to talk about it. Telling the story of her parents’ death through photography, she says, was a way of processing her loss and grief, but it was also, she says, a way of connecting with others and drawing on the power of community at a time when she needed it most.

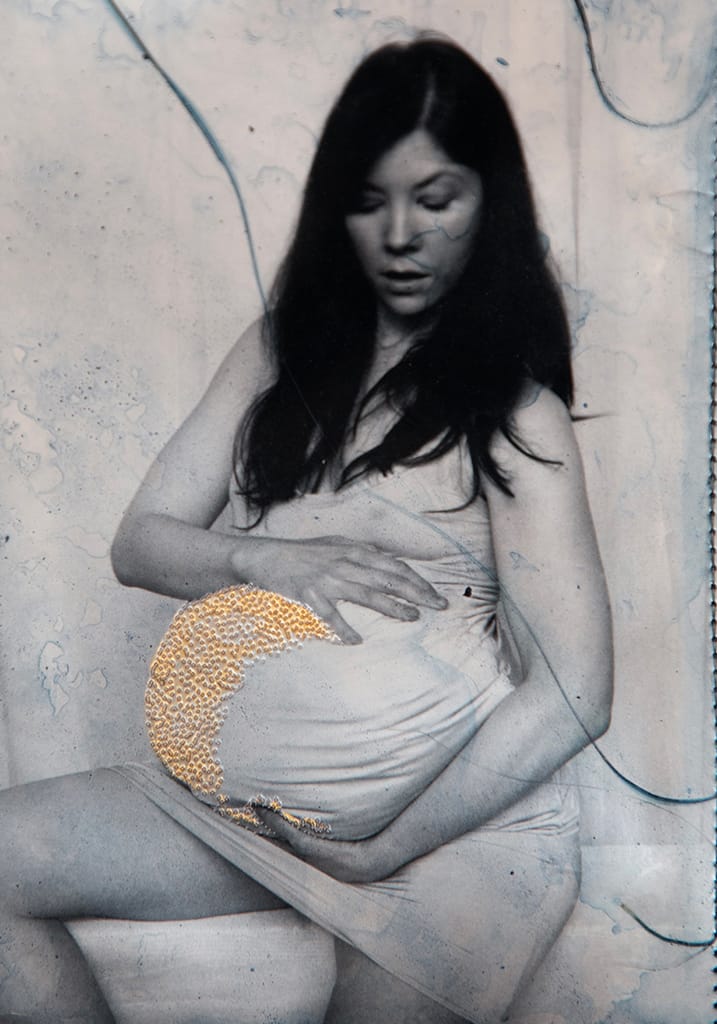

Now, Nancy—who is a mother of two boys and lives on the tiny Caribbean island of St. John—is preparing to show her latest project in Brooklyn, N.Y., a public exhibition profiling women in the U.S. who have experienced stillbirth.

“The fact that stillbirths are still so common in the U.S. when so many of them could be preventable, is a tragedy,” she says. “I want my work to raise awareness of this and also to help people understand the power of talking about loss and grief as a way of healing.”

This conversation has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

You’ve covered all kinds of subjects all around the world, but it seems the projects closest to your heart deal with the experiences and emotions people find most uncomfortable: death and of grief. What draws you to these topics?

I'm a very positive person, but when my parents were dying and I was spending time with them, photographing them, advocating for them, and having really deep, meaningful conversations with them—the type of conversation you can only really have when someone is dying—I realized that there was so much value in telling these stories and not being scared of the inevitable; not being scared of death.

Culturally—in the U.S. at least—we tend to be scared of illness and death. And I think that by not talking about these things, we’re doing a great disservice to our family and friends and those around us. There's so much dignity and grace at the end of life, and there are so many lessons to be learned.

I also photograph things that are very joyful. For years I've been photographing dogs and the humans who own breed and show them. And I actually think this is all connected. It's all about feeling and connecting and it’s about how people define family—how people find joy in all the moments; both the good and the bad.

Your latest project, “The Loss Mother’s Stone,” chronicles women’s stories of stillbirth. What moved you to do this type of work?

I have not personally experienced stillbirth, but I was drawn to these stories because, after losing my parents 364 days apart from terminal cancer, I was very aware of the deep feelings of grief and loss and sadness and all of those things that come after you've lost someone you love.

I was also grappling with my own postpartum depression that followed the birth of my first son, a healthy baby boy.

I knew that photographing my parents had helped me process my grief when they were sick. And so I thought, maybe if I tell stories about birth trauma I might feel less alone. So I posted a question to Facebook, as one does, asking if people had stories about birth trauma they wanted to share with me.

Many people wrote back, and one woman asked if I was thinking about including stories about stillbirth. Frankly, stillbirth had not even crossed my mind. I didn’t know much about it. But I quickly learned that it is more prevalent in the U.S. than I had known. One in every 175 pregnancies in the U.S. ends in stillbirth, which, in the U.S., is considered after 20 weeks gestation. That's 20,000 stillbirths a year. Doing more research, I found that while many countries have reduced their stillbirth rates by 20 to 30% over the last 20 years, the rates in the U.S. have declined by less than 10%.

There are preventable measures that can change the outcome for many expectant parents, but in the U.S., preventative medicine is, sadly, not the way.

I started talking with women who had experienced stillbirth, and I became so angry. Many of these women shared that their pain was ignored, their concerns weren’t taken seriously, and they felt invisible near the end of their pregnancies.

I also felt a deep connection with these women. I could identify with the grief that they felt. But also, as a new mom, I could understand some of what they had gone through. I realized how lucky I was to get to walk away with a healthy baby.

Tell me about the title of the work, “The Loss Mother’s Stone.”

As someone with a background in photojournalism, my instinct is to document what I'm seeing—to capture what's happening in front of me and let that tell the story.

In this situation, I was asking women to tell me stories that happened in the past, and this can be really difficult to portray visually.

Early on, I decided to tell this story in diptychs. I wanted to make a beautiful portrait of each mother, because let's be honest, moms are never in the photo. I wanted to create an empowering portrait and to pair it with a detail shot of an object or something that symbolized, not just the child that they lost, but their journey after that loss.

It’s telling you the story without showing you the graphic images of the stillborn children, which are devastating and, frankly, easy to turn away from.

When I started thinking about what to call this project, I came up with lots of different ideas, but everything felt, not quite trite, but perhaps a little obvious. I wanted something that had layers.

There’s a tradition in Jewish culture of placing a small stone on a grave as a quiet act of remembrance and a gesture of respect. You don't leave a flower because it will wither and fly away. Instead, you leave a rock and not only will it stay in place, but it represents this permanence and this reminder that this person existed and was loved.

The women themselves are in some ways like these rocks, too. They're strong, they're unmoving, and they will always remember.

I hoped my photographs would serve a similar function, but also, the women themselves are in some ways like these rocks, too. They're strong, they're unmoving, and they will always remember.

You’ve spoken in the past about the therapeutic value of photography. Tell me about that.

The therapeutic value, to me, is the connection between those viewing the photographs, the person making them and the people involved in them—perhaps those depicted. It’s about the human connection.

I worked on the majority of this project while I was pregnant with my second son. I initially wondered whether it was a good idea to be working on a project about child loss when I was trying to grow my own. But, it actually made me feel really empowered.

Also, the women I worked with were incredibly supportive. I felt such a special bond with them: They had so much to share and what they shared was so valuable. Through my work, I hope to pass on all of that knowledge too. I want this project to be a resource for pregnant people—for anyone really—to support people in their pregnancies, and in their losses.

What else is on the horizon for you?

I'm so excited that “The Loss Mother’s Stone” is finally going to have life in a public-facing way. I want to share it as much as I can and as widely as I can. But I’m also a mother of two young kids which means I'm perpetually trying to figure out this dance between mothering a 2- and a 5-year-old while living on a remote island and also doing work that’s meaningful to me.

I've come to realize that everything is seasonal and you just don't know what the future holds. I do want to keep shooting, but I don't think I have the capacity to dive deep into another big project right now.

Instead, I'm leaning into work that exists in the world that I'm living in. I'm doing a lot of family photography, some weddings and even attempting to document my own family, which as any parent knows, is easier said than done because we just don’t have enough hands, or hours. It's nice to photograph other people's joy and our own joy and then to still have time to make lunch boxes, do laundry, get sleep and, who knows, perhaps even have a shower.