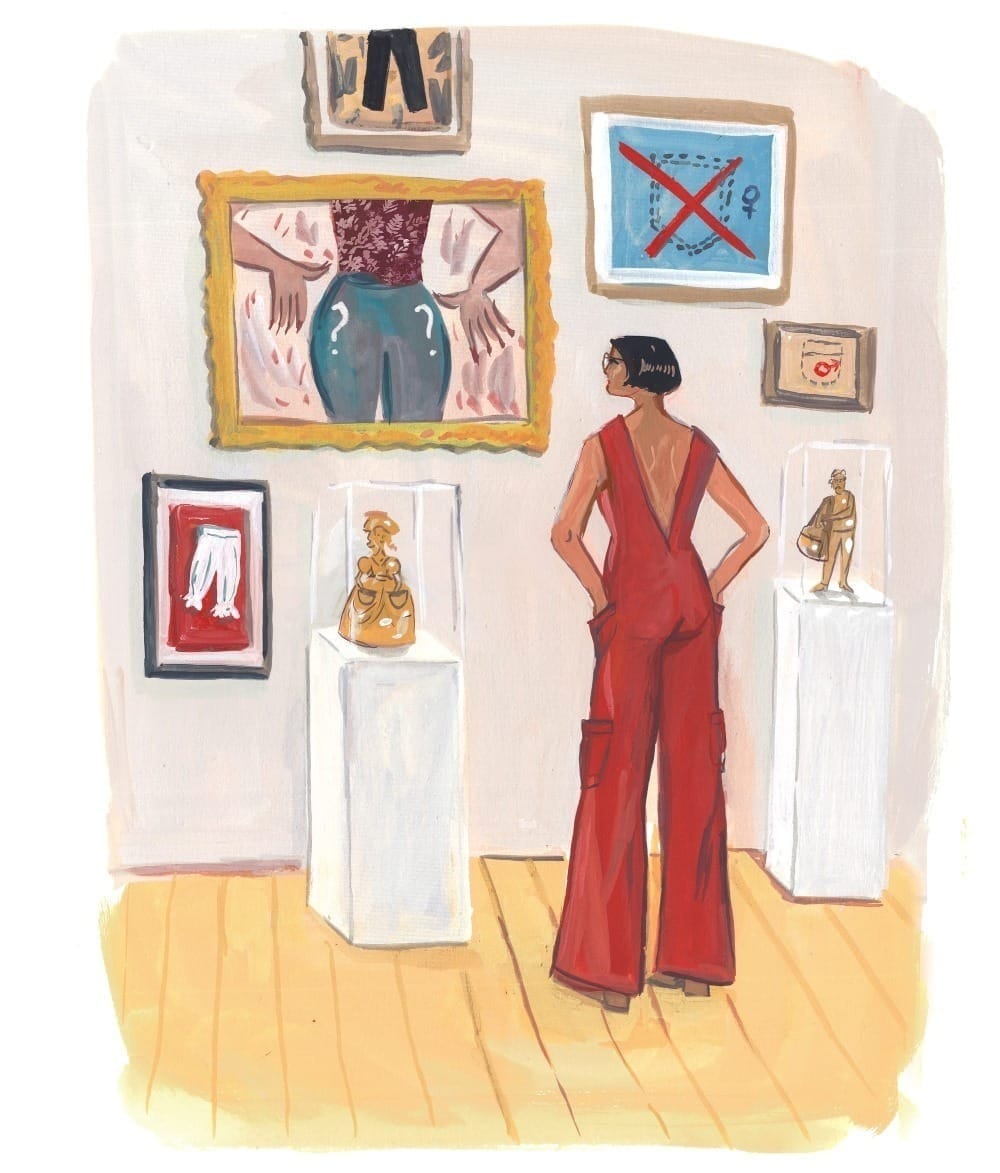

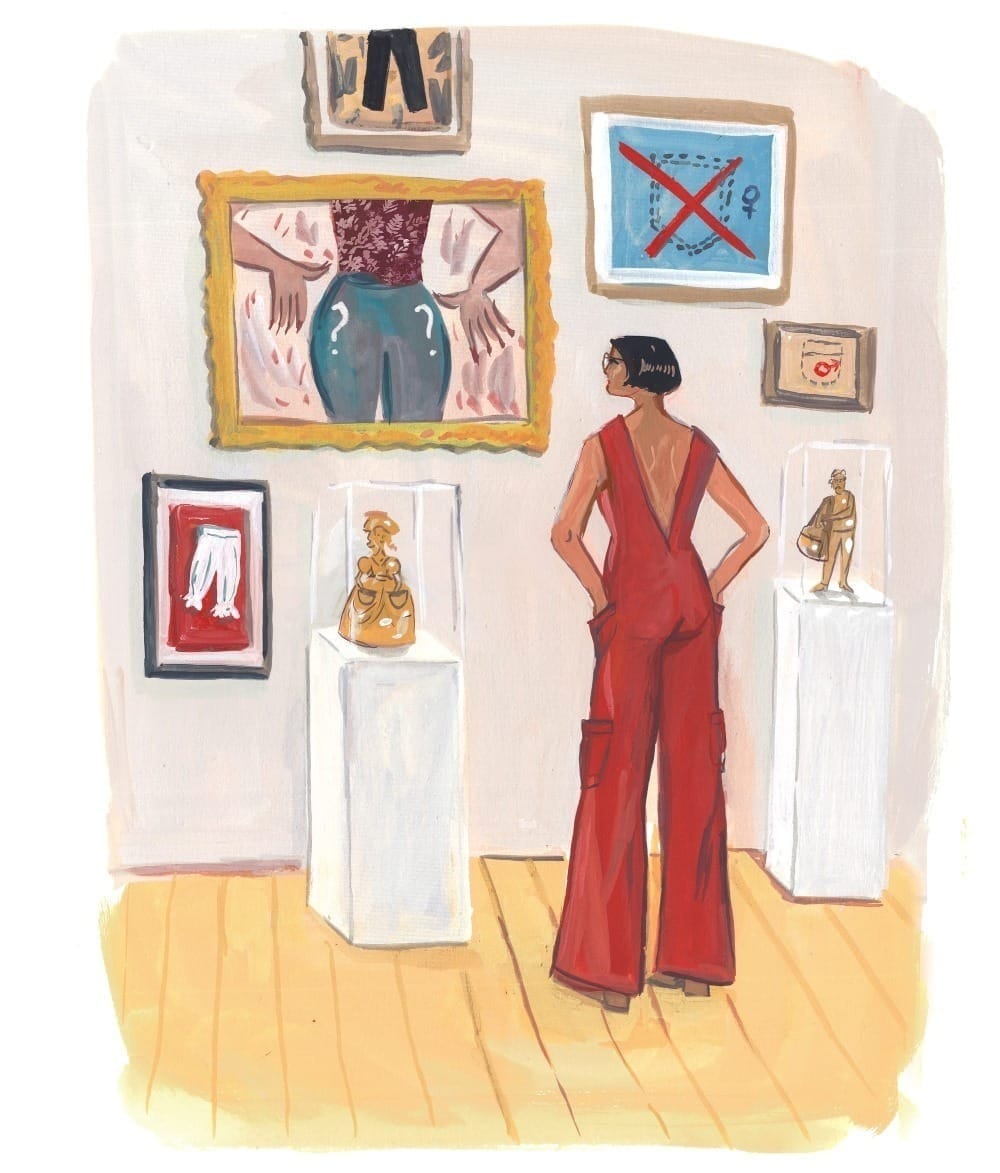

How Everyday Sexism Is Sewn Into Our Clothes

Pockets should be a given—as essential as elastic in our underwear or buttons on our coats.

Pockets should be a given—as essential as elastic in our underwear or buttons on our coats.

Creativity shouldn't be about success. It should be about the simple joy of trying something out.

Coverage of Jeff Bezos compared with Lauren Sánchez is highly gendered. He is a man with an ‘achiever mindset’. She is…’bikini-clad.’

Making the case for being OK with just being OK.

Ten years since the Supreme Court's ruling in Obergefell, how do things look for LGBTQ rights?