Lilly Ledbetter Has Made It to the Big Screen. It’s About Time.

It took the writer and director Rachel Feldman years of doors being slammed in her face before she got her movie off the ground, but she’s finally done it: LILLY is out May 9.

“Even though I had some of the best production numbers on record, management always found ways to demote me back to the floor. It was hard, working in that place. Hard being a woman. It felt like walking in a minefield. Never knew when I'd take the wrong steps. Nineteen years, things only got worse.”

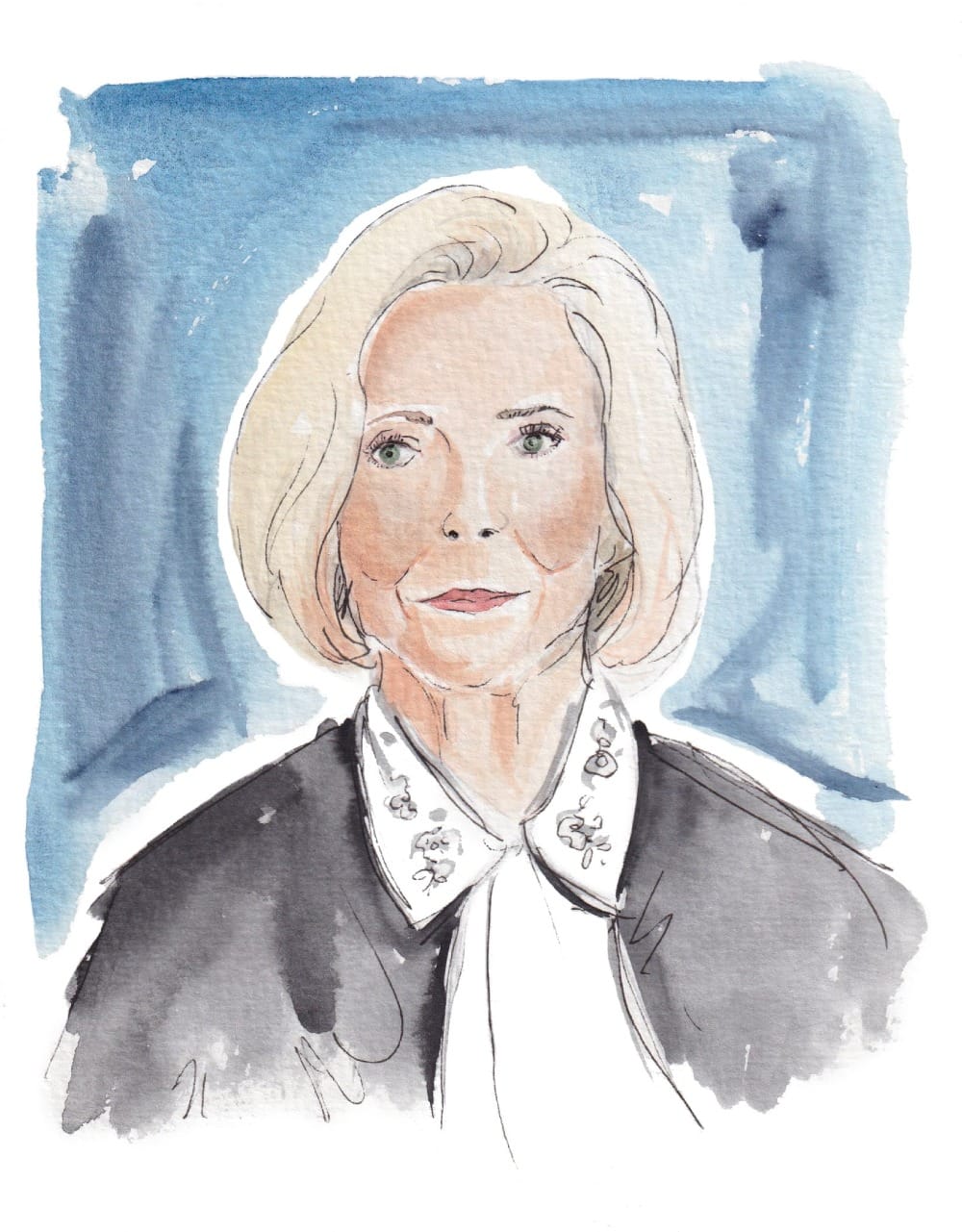

— Lilly Ledbetter, as played by Patricia Clarkson, in the movie LILLY

We’ve all heard them: the messages—sometimes subtle, sometimes overt—that you don’t quite measure up. Perhaps you’re not smart enough. Or your ideas aren’t all that. Or your skills are slightly lacking. You’re good, let’s be clear about that. In fact, you might be very good. You’re just not good enough.

Lilly Ledbetter certainly heard it in her nearly-two decades at the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company. She was hard-working and advanced quickly, but it didn’t matter. She was the wrong person in the wrong industry at the wrong time, snatching away a job that should have gone to a man. She was made to pay for it, earning far less than her male peers. She was insulted and abused for years.

The Goodyear plant in Gadsden, Ala. where Lilly worked in the 1980s and 1990s, might feel like light years away from Hollywood of the 2010s and 2020s, but it’s not. In Hollywood, sexism persists, doors are slammed in faces. Of the top-grossing films in 2023, just 12% were directed by a woman. By comparison, in 2007, that number was shy of 3%. So it’s progress, but for goodness’ sake, it’s not much.

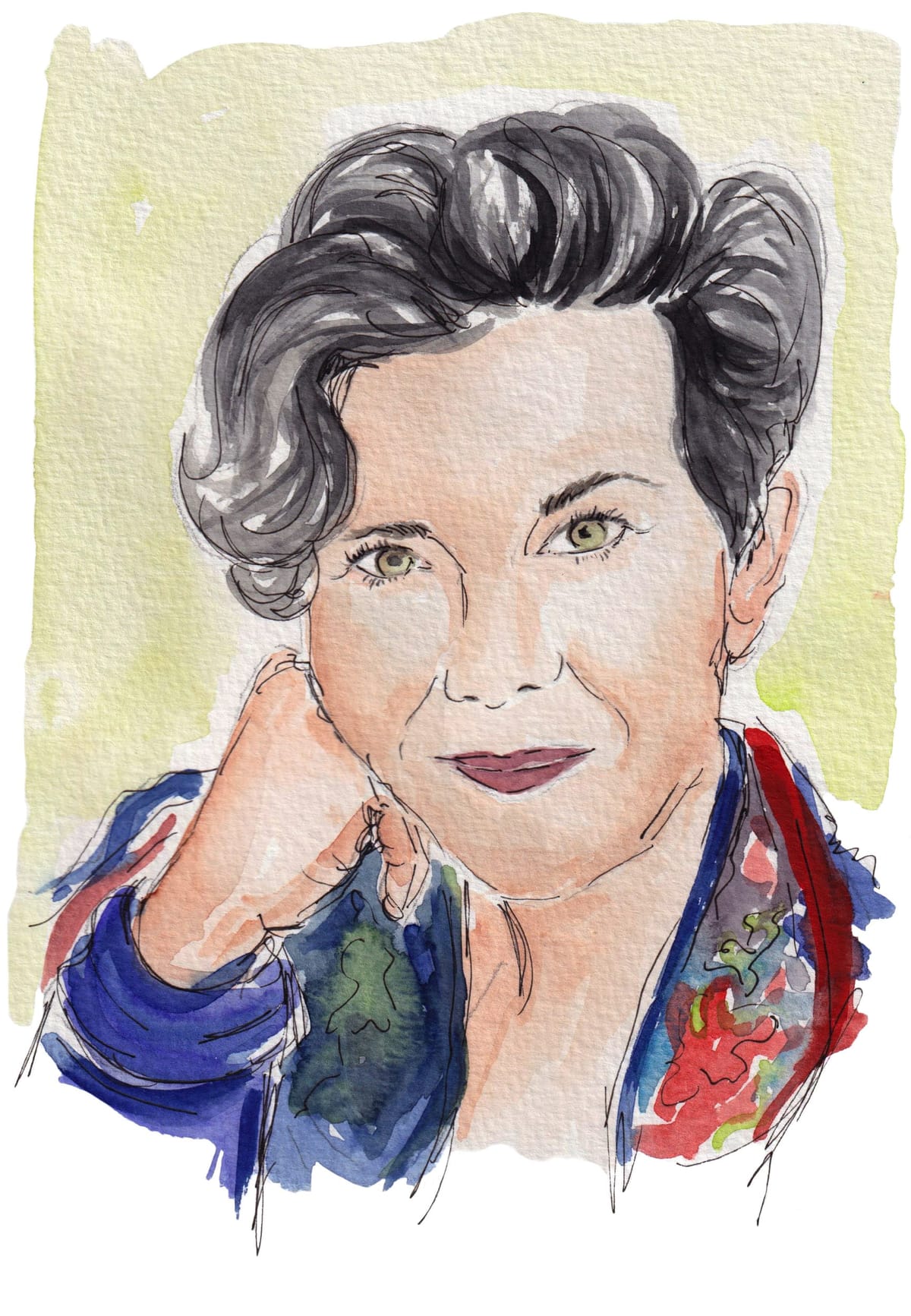

Perhaps that is why Rachel Feldman is such a fitting director for Lilly Ledbetter’s story. Feldman spent years in front of the camera as a child actor (also, she was the voice of Lucy in Peanuts) and she studied at Sarah Lawrence, Parsons School of Design and attended the NYU Graduate Film program, but still it took her a decade to land her first job. “It was nothing but rejection for years on end, slammed doors, no access, no matter how hard I tried. It felt like being locked outside of the gates of a kingdom,” Feldman said in a Tedx Talk.

Lilly was told no thank you, so was Feldman.

But persistence, right?

And here we are. Come May 9, the film “LILLY” (tagline: One fearless voice is all it takes) will be shown at over 40 theatres across the U.S. Starring the perfectly-cast Patricia Clarkson as Lilly, it’s something of a crown on Lilly’s life. How very fitting indeed.

I spoke with Feldman, who optioned the rights to Lilly’s story, wrote the screenplay, and spent years trying to get the movie made. We discussed what it was like to work with Lilly and why Hollywood remains so fraught for women.

Our conversation has been condensed and lightly edited.

Why Lilly?

When I saw her speak on television at the DNC in 2008, I had a physiological response. A little voice inside of me said, “This is an incredible woman.” I didn't know much about her at that time, so it truly was a gut instinct. But the more I pursued it, the more I discovered a truly incredible story. Not just the things that we know about her in terms of her political and social relevance, but her own personal story, which was really the thing that was most interesting to me.

Tell me what Lilly was like.

I'll start by saying that Lily was a joy to work with at every level—positive, hopeful. She ended every email and conversation by saying that she had faith in me, even when it took, you know, more than 10 years to get the movie made. And we had plenty of hills and valleys and ups and downs. She was always positive. Now, keep in mind, I met Lilly towards the end of her life; after she had succeeded. And that's the story that was interesting to me as a filmmaker: a woman who was badly treated and had a frustrating experience trying to achieve justice for herself, who managed to transform herself into a voice, into an activist, so that she could make change for others.

You know, Lilly said that all she really wanted was to have a life of meaning. That's what she wanted, and that's what she got.

You know, she said that all she really wanted was to have a life of meaning. That's what she wanted, and that's what she got.

Who is going to watch this movie? Who is going to review this movie? It's a really painful question, and frankly, not one that I really want to ask. But it's also important.

My goal with the film was to make pure entertainment. My goal was to make a popcorn movie. My goal was to make a movie that everyone will enjoy once they get themselves into the theater or in front of the screen. My goal—and it's a cliche, I say this all the time, but I'll say it to you too—my goal was to make a rollercoaster ride of suspense, heartbreak and euphoria, which I think every good movie should be. And I think that I am giving the audience that.

I've just come off of a very successful festival tour with theaters filled to the brim. And I have had men come up to me with tears in their eyes, thanking me for making this movie.

It’s a movie about a woman, but it’s also about men…

Lilly would not have been able to achieve what she achieved without two very important men in her life. Her husband, Charles, and Jon Goldfarb, her attorney, who was a young civil rights attorney in Birmingham, Alabama.

Goldfarb looked at her and saw her for who she was, not just the aggrieved factory worker or the country bumpkin. She came from Possum Trot; from a home without electricity and running water. She stepped over snakes to get to the outhouse. But she was a formidable, highly intelligent human being. And Jon Goldfarb saw that immediately and was her advocate, and he's still her advocate. These two men are central to her story. And I think they're central to our stories, because women are not going to be able to achieve the things we need to achieve unless the men who love us have our backs.

Let's talk about sexism in Hollywood, which of course you know very well. Talk to me about what gets made, what doesn’t get made and who gets to make films. Start with Barbie?

There is certainly a gender factor in terms of what's interesting to Hollywood. But there’s another factor, too, and that’s this element of celebrity. If Greta Gerwig didn't want to make the film about Barbie, it would never have gotten made. (I pitched Barbie 30 years ago, and they were like, “what?”) If you are the right woman, you can get things going. But there are so few women that are considered powerful women. That's really the issue. It’s Kathryn Bigelow and Chloe Zhao; Patty Jenkins who did Wonder Woman.

Often it’s not the idea itself, it's who's pitching it. It took Greta Gerwig to get "Barbie" made.

But there should be 500 women who should be able to pitch an idea. Often it’s not the idea itself, it's who's pitching it. It took Greta Gerwig to get "Barbie" made.

Is that why it took you 10 years to get Lilly made?

I first went to Lilly in 2008. She was in the middle of writing her book, which I optioned. I wrote the screenplay very quickly and I started winning some awards with the screenplay very quickly, which made me a little bit confident.

And over the course of the next five years, I optioned the script about five times to five very prominent, well-known, sometimes Academy Award-winning producers. None of them could get the movie off the ground. I don't know that any of them really tried.

At one point, a producer told me, “I won't be able to get this movie made unless a man directs it.” And at that moment, I said to her, well, “La dee da, it’s lovely knowing you,” and I walked out with my head held high. But I felt such pressure because I wanted to produce this for Lilly and for Jon Goldfarb. I had promised them; they believed in me; I convinced them that I could do it.

Then several doors flew open at the same moment. I met my business partner, who said to me, I know how to raise money for films. And we put our financing together relatively painlessly. And here we are on the brink of opening.

There’s an undercurrent of angst in the film. Is it something you were trying to convey? Or just my interpretation?

Many of us who have grown up underestimated and excluded have a chip on our shoulder. We are that little girl who is a people pleaser; and we are also these gigantic, well-formed female adults, monolithic statues, characters who have supreme confidence and ability, and yet are silenced so often and put down and not admired and not acknowledged and appreciated in the way we should be. So I think that angst is the constant state of not knowing whether this is going to be the right room for me; that this is the right moment for me. And yet, it's always there.

The Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act was signed into law in 2009 by President Obama, but is the Fair Pay act enough? Somehow it doesn’t feel like enough.

The way the government works is little by little. The Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009 was an important step. It’s not a huge fix. But I don't think anyone should roll their eyes at that or minimize it in any way. Here’s this girl who grew up without electricity and running water.

She picked cotton at the age of 8. And that was a good day's work. And she was proud of it. And there was no, “Do I look fat in these jeans?” That was so magnificent about her. She had confidence; she was grounded.

I look at the story of Lilly—a woman in the wrong place, doing the wrong job at the wrong time; fighting her way through. There's this parallel to you in Hollywood, breaking down doors as best you can, but being told no thank you over and over. Lilly’s story is our story. So is your story: Wrong person, wrong time, wrong name, wrong height, wrong looks, wrong outfit, wrong hairstyle, wrong everything. And it's not about talent; it's not about ability; it's not about skill. Thoughts?

What Lilly did in her life is she became an activist. She was able to take all of that negativity and turn it into something positive. Because when we fight for other people, it's so much easier than fighting for ourselves. All those things that you just said about me as a filmmaker are 100% true. I turned my sadness and the grief I felt for not being acknowledged into a fight for other women. I fought for us as a group by illuminating the issue. And I'm very glad I did that. It was a very healthy thing to have done. And so what I would say to everyone else is: Stand up, speak out, do the right thing. And it actually heals you when it's not all about your personal issue.

Nobody singled me out and nobody really singled out Lilly. And maybe Lilly was actually the right person at the right time, and I might be the right person at the right time. And you might be the right person at the right time, because we all need to take whatever injustice we are experiencing or seeing and we need to be the ordinary person who does the extraordinary thing.

Find out how to watch Lilly at a theater near you.