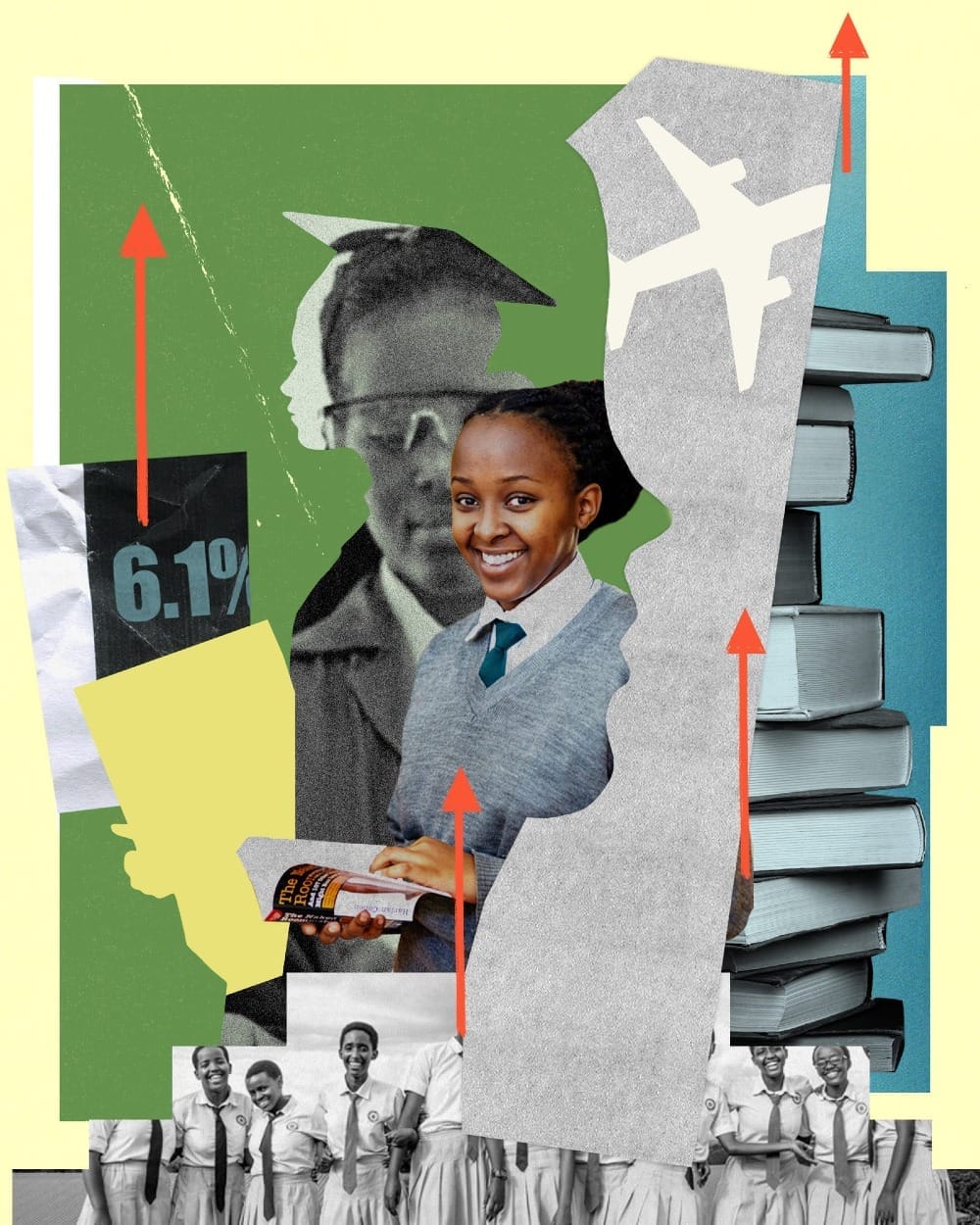

All’s Well In School. But Come University, Rwandans Wonder: Where Are the Women?

Rwanda’s young women aren’t making it to university. Cultural and societal factors are to blame.

The Persistent is available as a newsletter. Sign up here to get it delivered to your inbox.

Growing up in Kigali, Peace Ndoli Iraguha was tenacious, driven, determined—and smart. She fit right in as a student at the prestigious Gashora Girls Academy of Science and Technology and never doubted she’d go on to university.

Everything went to plan, but there was one surprise: When Iraguha stepped on campus at the University of Rwanda, she found herself wondering where all the women were.

Just one-third of the students overall at the University of Rwanda are women; with those numbers rising or falling depending on the specific college.

Iraguha was in the College of Medicine and Health Sciences, where there was a slightly better gender balance than some of the colleges, she explains. But at the School of Engineering, Iraguha estimates that a mere handful out of her grade of some 50 students were women.

The numbers fell further as women dropped out to get married or because they were pregnant, said Iraguha. “Every single time we came back from break, there were fewer women in class.”

The gender gap Iraguha observed at her university is not uncommon. In fact, it extends across all tertiary education in Rwanda. But it’s a gap that persists despite the country’s long-standing efforts to promote girls’ and women’s inclusion in education as well as society more broadly.

In the three decades since the country’s genocide and civil war, the Rwandan government has recognized that while it has more young women than men completing secondary education—indeed girls are outperforming boys at various levels—the numbers of young women going for higher education have remained below the African average.

World Bank data from 2024 show that just 6.1% of women in the country go on to tertiary education, compared with 7.9% of men. In 2019, just 27% of STEM students in Rwandan higher education public institutions were female, while only four in 10 students enrolled in tertiary technical and vocational education training (TVET) in Rwanda were female. (Though to be sure, the numbers for men are not particularly high either as many skip university to start work in Rwanda’s agriculture-based economy.)

Rwanda, of course, is not unique in this: According to UNESCO data, just 8% of women across Sub-Saharan Africa are enrolled in tertiary education versus 10% of men. But for a country that has made good strides in gender parity when it comes to primary and secondary education, the numbers are surprisingly low.