Why Can’t We Just Pass the ERA? It’s Complicated.

The Equal Rights Amendment is a simple 24-word piece of legislation. But it’s also a historic movement, more than a century in the making, that began with women’s suffrage and continues to this day.

Over the past few weeks, as equality advocates have called on President Joe Biden to use the final days of his presidency to publish the Equal Rights Amendment, many questions have been asked about the legal hurdles for ratification and what—despite a century-long fight—is still preventing gender equality from being enshrined in the United States Constitution.

Amid the chants, banners and bumper stickers, it’s important to remember that the ERA is so much more than a 24-word piece of proposed legislation. It’s a movement—years in the making, defined by grit, gumption and persistence—of 20th century feminism, of precedent-establishing court decisions, of women’s suffrage, and of individuals who dedicated their lives to making the U.S. a fairer place for all.

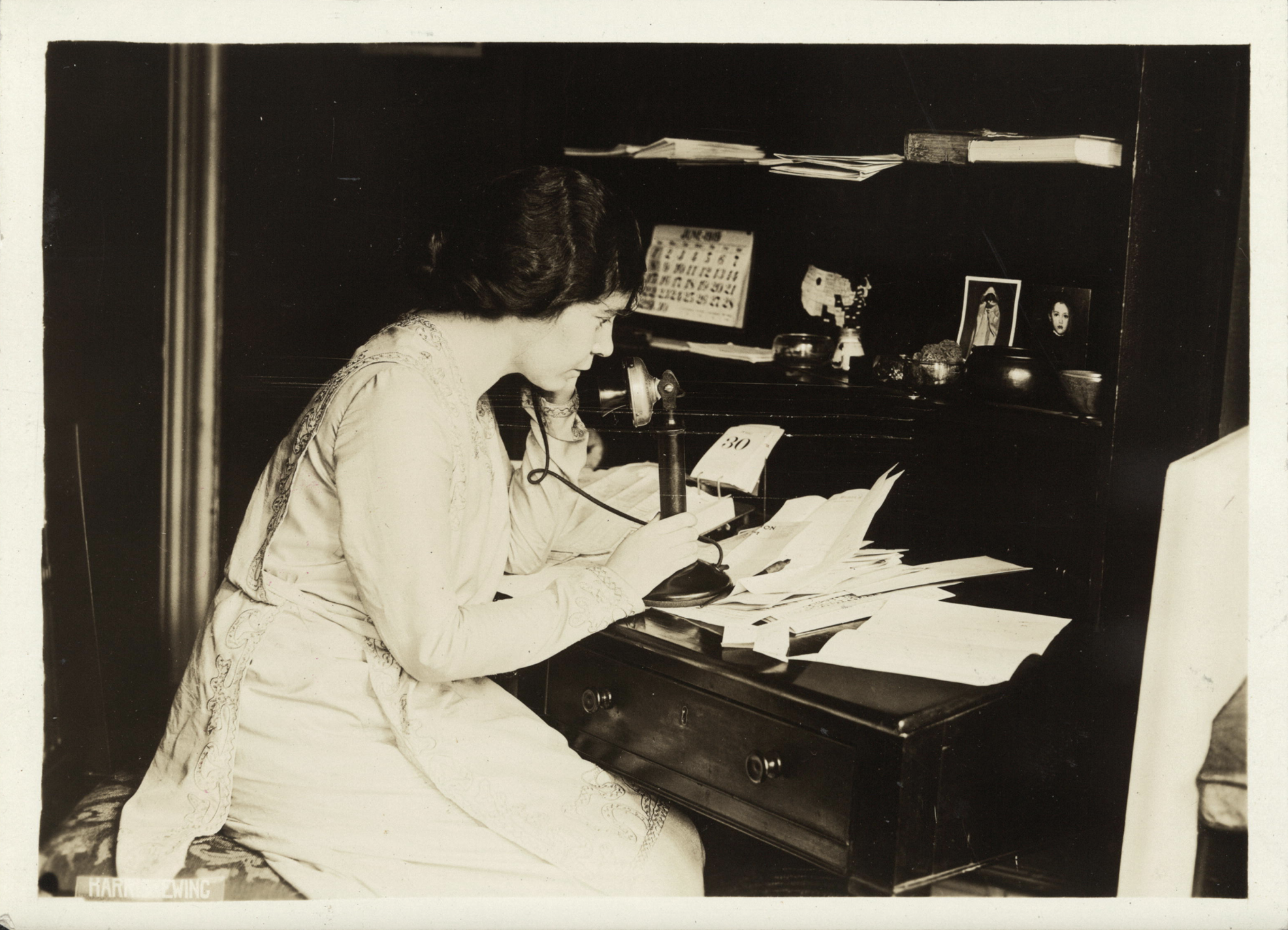

One such individual was Alice Paul.

Hello, Alice

Born in January 1885 in Burlington County, N.J., Paul was the first child of William and Tacie Paul, Quakers who raised their four children according to their faith’s staunch belief in gender equality. From an early age, Paul’s parents impressed upon their children that, regardless of gender, each had a duty to contribute to the betterment of society as a whole.

The Quaker belief in gender equality was unusual at the time, but helps to explain why so many of the individuals who were active in the fight for women’s suffrage were Quakers.

Paul attended a Quaker school in Moorestown, N.J., and then enrolled at Swarthmore College, a co-ed school (also unusual at the time), co-founded by her maternal grandfather. She excelled academically and was inspired by many of her teachers, including a mathematics professor named Susan Cunningham, who would later become one of the first women to be admitted to the precursor organization to the American Mathematical Society.

Lessons from Pankhurst

After her graduation, Paul moved to New York City, where she developed an interest in the emerging field of social work, learning about the detrimental effects of economic and gender disparities on communities. In 1907, she earned a Master’s degree from the University of Pennsylvania, where she studied political science, sociology and economics. Almost immediately after that, she moved to England, where a small group of militant suffragists was attracting media attention for resorting to violence to raise public awareness of their demands for equal rights.

There, she struck up a friendship with Christabel Pankhurst, the daughter of Emmeline Pankhurst—widely credited with leading the charge for women’s suffrage in the United Kingdom—and joined their movement. The women were regularly arrested for smashing windows and other acts of civil disobedience, which on several occasions landed them—including Paul—in prison. When that happened, they staged hunger strikes and were force-fed, which captured the attention of the media.

“The militant policy is bringing success,” Paul wrote of the strategy that Pankhurst and her fellow suffrage campaigners were using when she returned to the U.S. in 1910. “The agitation has brought England out of her lethargy, and women of England are now talking of the time when they will vote, instead of the time when their children will vote, as was the custom a year or two back,” she added.

Fighting for Suffrage in America

Upon her return to America, Paul re-enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania, this time in pursuit of a Ph.D. She also joined the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), formed in 1890 as a merger of two rival factions, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), led by Lucy Stone, Henry Blackwell, and Julia Ward Howe. Soon Paul was appointed head of the group’s Congressional Committee, effectively putting her in charge of leading a federal suffrage movement.

In 1912, Paul moved to Washington, D.C., where she collaborated with other NAWSA members, including Lucy Burns and Crystal Eastman, to organize a massive women’s march for nationwide suffrage on March 3, 1913, the eve of Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. Crowds of outraged onlookers, mostly men, heckled the thousands of parading women who’d traveled from across the country to be there. The march was swiftly brought to a violent end, but it drew extensive media coverage, alerting the public to the women’s demands and introducing the issue of voting rights into mainstream conversation and consciousness.

Paul had been working closely with NAWSA’s president Carrie Chapman Catt in the lead-up to the march, but as time went on, the differences in their political strategies and approaches became evident. Paul believed that pushing for constitutional change was more important than Catt’s focus on state campaigns. Their disagreement proved irreconcilable, and in 1914, Paul and a group of women who championed her strategy split from NAWSA and two years later established the National Woman’s Party (NWP).

‘How Long Must We Wait?’

Inspired by Pankhurst’s grit and willingness to throw physical and metaphorical rocks, the NWP in 1917 organized the first-ever public picketing in front of the White House. So-called Silent Sentinels bearing protest banners stood outside the gates of the White House to shame President Wilson for his inaction and apathy on the cause of women’s rights. NAWSA, as an organization, endorsed President Wilson, but Paul considered him and his fellow Democrats in power to be responsible for female disenfranchisement.

“Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?” one banner read.

Six days a week, irrespective of inclement weather, the women congregated in nonviolent protest. Quietly they stood in defiance of passersby who peppered them with half-hearted heckles and insults. At first, Wilson treated Paul and her fellow protestors with condescension or simply ignored them, but as the months drew on and the women persisted, tensions between the NWP and Wilson rose. When America entered World War I, a shift occurred.

The suffragists who, until that point, had been regarded by many as a nuisance at worst—pesky gadflies—suddenly drew wrath from members of the public who considered their actions to be entirely unacceptable and insultingly disloyal to the country. Angry mobs of mostly men started insulting them and during the summer of 1917, while they were still protesting non-violently, some of the women were arrested, purportedly for the crime of obstructing traffic.

As had happened in England, Paul was imprisoned later that year and, upon starting a hunger strike, she was force-fed. Well over a hundred women were arrested and kept in freezing, unsanitary, rat-infested cells. Paul ended up being moved to a sanatorium, where prison officials hoped she would be declared insane. Around that same time, however, information about the conditions under which the female prisoners were being held began to leak to the press. Appalled that anyone would be forced to live in such squalor, members of the public started to sympathize with the suffragists, demanding their release and exerting pressure on politicians to intervene.

When Paul was eventually released, she encountered a groundswell of support that was entirely new to her and that heaped pressure on President Wilson to seriously entertain the idea of supporting votes for women.

Finally, at the end of 1917, he did. In the subsequent months, Wilson met with members of Congress to drum up support for a suffrage amendment, presenting it as a “war measure.” The war, he claimed, couldn’t be fought effectively without female participation. In 1919, members of the House of Representatives and the Senate voted to pass the 19th Amendment, which was sent to the states for ratification. Three-quarters of states were needed for the amendment to pass, and in the summer of 1920, with 35 states having voted to ratify the amendment and 36 needed, the deciding vote landed on Tennessee.

In the end, it came down to a young man named Harry T. Burn who on the advice of his mother, declared his historic “aye” and the battle for women’s suffrage was over.

A New Chapter

After the enactment of the 19th Amendment, many suffragists turned away from activism and public life considering their work to be done.

Not Alice Paul.

Undeniable progress had been made in August 1920, but Paul knew that gender equality was far from guaranteed.

In the years that followed, she earned three law degrees at the American University in Washington, D.C., arming herself with the skills, experience, and reputation to craft legislation. In 1923, Paul announced that she had authored what she called the Lucretia Mott Amendment, in homage to the abolitionist she so admired. The amendment called for absolute gender equality and stated that “men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction.”

Every year from 1923 until 1942, Paul and her supporters submitted the Lucretia Mott Amendment to Congress. It never passed. In 1943, with her patience running thin, Paul reworded the original draft to better reflect the language of the 15th and 19th Amendments, which she hoped would make it more palatable to lawmakers. The new version stated that “equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.” It became known as the Alice Paul Amendment, and Paul continued to submit the revised version to Congress annually.

Equality For All

As Paul aged, a new cast of characters took up the baton in the fight for gender equality.

In an August 20, 1969, memo to President Richard Nixon, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, an assistant to the president on domestic policy—despite not referring explicitly to the ERA—observed that “the essential fact is that we have educated women for equality in America but have not really given it to them. Not at all.” He asserted that “inequality is so great that the dominant group either doesn’t notice it or assumes the dominated group likes it that way,” and he urged Nixon to consider what it might be like to have a woman as president. “Male dominance is so deeply a part of American life that males don’t even notice it.” Nixon did eventually become a fierce advocate for the amendment.

Betty Ford, even beyond her relatively short term as first lady, was a champion of the ERA. At the 1980 Republican National Convention, when a debate commenced over the removal of the ERA from the GOP platform, Ford stormed out of the convention and joined the National Organization for Women’s protest outside. Other conservative women publicly supported it, too, including the Supreme Court justice, Sandra Day O’Connor. But it was the New York State congresswoman Shirley Chisholm who delivered perhaps history’s most impassioned endorsement of the ERA.

In a speech in 1970, Chisholm described the ERA as “one of the most clear-cut opportunities” that Americans were likely to have to declare their “faith in the principles that shaped our Constitution.” She noted that, while “prejudice on the basis of race is, at least, under systematic attack,” discrimination against women purely on account of their gender “is so widespread that it seems to many persons normal, natural, and right.”

Chisholm reeled off a laundry list of rights that women were still denied: “Women are excluded from some state colleges and universities,” she said. “In some states, restrictions are placed on a married woman who engages in an independent business. Women may not be chosen for some juries. Women even receive heavier criminal penalties than men who commit the same crime,” she went on.

She took aim at labor laws ostensibly designed to protect women. Ultimately, she said, “artificial distinctions between persons must be wiped out of the law. Legal discrimination between the sexes is, in almost every instance, founded on outmoded views of society and the pre-scientific beliefs about psychology and physiology. It is time to sweep away these relics of the past and set future generations free of them.”

‘Never Underestimate the Power of a Woman’

By 1970, about half of all single women and 40% of married women in the U.S. were working outside the home in paid employment; this fueled swelling discontent with the barriers still faced by this growing portion of the labor market. That same year was also the 50th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, but rather than celebrating, many supporters of the women’s movement seized on the half-century milestone to draw attention to how little had actually changed since Harry T. Burn had cast that all-important vote in 1920. In 1920, not a single woman had been in Congress. In the span of 50 years, that number had risen to just 11.

The average woman working full-time, year-round still made only 59 cents for each dollar a man made in an equivalent job. And even though outright discrimination had, in many respects, been outlawed, it was still rampant, fortified by habits, beliefs, and a culture of misogyny that underpinned many industries and organizations. Until the 1970s, marital rape was not a crime. And as late as 1977, two-thirds of Americans believed that it was a man’s job in a household to earn money, while women should be responsible for taking care of the home.

Betty Friedan—by then 49 years old and divorced—was among the feminist leaders whose frustration was boiling over. Much of the criticism she’d leveled at society in her bestseller “The Feminine Mystique” had remained unaddressed, something that over a hundred feminists decided to spotlight on March 18, 1970, when they marched into the offices of the magazine, Ladies’ Home Journal, one of the leading periodicals of the time, to protest the way in which the magazine’s mostly male staff—managed by a male editor-in- chief—depicted women’s interests and aspirations. An irony the protestors enjoyed underscoring was that the magazine’s motto was “Never Underestimate the Power of a Woman.”

The demonstrators made concrete suggestions including that the magazine hire a female editor-in-chief, provide free childcare for its staff, and put an end to the “basic orientation of the Journal toward the concept of Kinder, Küche, Kirche”—a reference to the Nazi propaganda slogan widely used to describe the ideal woman’s purview in society: children, kitchen, and the church.

Two days later, Friedan called for a Women’s Strike for Equality to be hosted simultaneously in cities across the country on the anniversary of the passage of the 19th Amendment.

What followed her call was a series of planning meetings in New York to which all kinds of women’s groups were invited. The attendees, according to an account in The New York Times, resembled a cross-section of the city’s female population. “There were dumpy, gray-haired grandmother types who arrived at the meetings toting shopping bags. There were braless, long-haired teenyboppers in T-shirts and jeans. There were well-groomed Pucci-ed and Gucci-ed women who looked as though they had just left the bridge table in Rye. And there were always a few Blacks—but never more than a handful.” Women were determined to make this march a day that would change history.

A March for History

The air in Manhattan on August 26, 1970, was muggy and oppressive, but it didn’t deter the crowds who poured in for the Women’s Strike for Equality. Thousands filled Fifth Avenue, many chanting, singing, and carrying signs. Organizers of the march had obtained a permit but paid no heed to the city order that it stay in a single traffic lane. The crowd exploded. “Every kind of woman you ever see in New York was there,” noted The New York Times.

Traffic stood still for hours as the streets were claimed by women who shared three distinct demands: free, around-the-clock childcare; equal opportunities in education and employment; and access to abortion for all. Friedan urged work stoppages to coincide with the march of “everyone who is doing a job for which a man would be paid more,” as well as of any woman doing unpaid domestic labor.

The roster of speakers included Kate Millett, a Columbia Ph.D. and the author of the bestselling book “Sexual Politics;” Congresswoman Bella Abzug, nicknamed “Battling Bella” for her fearlessly confrontational demeanor; and Eleanor Holmes Norton, a lawyer who had recently sued Newsweek for gender discrimination on behalf of dozens of female employees, and who demanded from the podium that the U.S. Senate pass the ERA. Even Alice Paul, frail at the age of 85, made an appearance.

Witnesses estimated that as many as 50 thousand took to the streets in New York City, with thousands more gathering in Boston, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, and hundreds more in places like Baltimore and Seattle. A newspaper in Louisiana reportedly replaced pictures of brides with pictures of grooms in the day’s wedding announcements to mark the occasion, while male preachers in Massachusetts asked women to make the sermons. Countless housewives turned their backs on their daily chores, refusing to cook, clean, and look after the children, shedding light on the extent of their unpaid—and often under-recognized—work.

Some hecklers in New York City, mostly men (of which a few mockingly wore bras), stood along the edges of the marching crowds, throwing pennies, but opponents on the day attracted little attention, and by the time the women congregated in Bryant Park in the evening, it was clear that the event had been a success. A CBS News poll found that four-fifths of all Americans had heard of women’s liberation in the weeks that followed.

Women’s Lib

“Women’s lib” would go on to become as frequently mocked as it was celebrated and as often criticized as it was championed. It was a label that was both derisive and complimentary and it came to sum up not just feminists who took to the streets with megaphones and placards, but an entire social movement. Women and supporters of gender equality had successfully forced policymakers, business executives, educators, and community leaders to acknowledge that they were serious in their demands and that they would not stop disrupting the status quo until change materialized.

As it turned out, that day in August 1970 did not result in the revolution that many had hoped for. The three core demands of the marching masses were not met as most women living in the U.S. today are likely aware. But it did raise awareness of the issues, and two years after the march, in March 1972—by which point Alice Paul was well into her 80s—the Senate and the House finally passed the ERA by the required two-thirds majority. For the first time, it truly looked like the 27th Amendment to the Constitution—now known as the Equal Rights Amendment, or ERA—could become a reality.

From there the proposed amendment was sent to the states for ratification. It would need 38 states to ratify. Congresswoman Martha Griffiths, the principal House proponent of the amendment, predicted that it would be “ratified almost immediately.” Congress placed a seven-year deadline on ratification. The countdown was on.

The Best of All Possible Worlds?

By 1973, 30 states of the required 38 had ratified the ERA. But then momentum slowed, curbed by a powerful alliance between conservative activists and the religious right. William H. Rehnquist, who would go on to become chief justice of the Supreme Court, warned that the ERA would “virtually abolish all legal distinctions between men and women” and “hasten the dissolution of the family.” Rehnquist wrote in a memo that within the women’s movement, there seemed to be “a virtually fanatical desire to obscure not only legal differentiation between men and women, but insofar as possible, physical distinctions between the sexes.”

Years later, Ruth Bader Ginsburg reflected that arguments against the ERA were also frequently rooted in a belief that women did actually have it better than men. “Judges and legislators in the 1960s and at the start of the 1970s regarded differential treatment of men and women not as malign, but as operating benignly in women’s favor,” she said. “Women, they thought, had the best of all possible worlds. Women could work if they wished; they could stay home if they chose. They could avoid jury duty if they were so inclined, or they could serve if they elected to do so. They could escape military duty, or they could enlist.” On these points, she considered it her mission to educate to the contrary both the public and the country’s decision-makers in the legislatures and courts. “We tried to convey to them that something was wrong with their perception of the world,” she said. “We sought to spark judges’ and lawmakers’ understanding that their own daughters and granddaughters could be disadvantaged by the way things were.”

Enter the Schlafly

And then there was Phyllis Schlafly—the conservative, anti-feminist, Harvard-educated attorney, who spearheaded a movement to block the ERA, claiming that its passage would lead to the introduction of, among other things, gender-neutral bathrooms and same-sex marriages.

Schlafly, who hailed from St. Louis, Mo., had entered electoral politics in 1952 in an unconventional manner. Republicans had encouraged her husband, John Fred Schlafly Jr., to run for Congress, but he turned them down. So Schlafly herself offered to run for Congress in her husband’s stead. Despite losing the general election, she rapidly gained prominence in conservative circles. She made countless speeches as an officer of the Daughters of the American Revolution, and she built and fostered a national network of hundreds of friends and acquaintances who shared her values and convictions.

During the early part of Schlafly’s political career, she barely even knew what the ERA was. And in fact, when she did learn about it, her initial inclination was to support it. But in December 1971, she read up on it and decided that it posed a serious threat to America’s sacred values and safety. In October of the following year, she founded and became chairwoman of STOP ERA, a precursor to the conservative Eagle Forum organization. The first part of the organization’s name was an acronym for “Stop Taking Our Privileges,” summing up concerns that the amendment would nullify earlier laws designed to protect women, guarantee alimony, and exempt them from combat. In fact, according to the U.S. Constitution, Congress at that point already had the power to draft both men and women into combat. Without the ERA, however, there was nothing that could provide a guarantee that women would be protected against sex discrimination in any professional field, including in the military.

By 1978, the ERA had still secured only 35 of the necessary 38 state approvals, so Congress by a simple majority, extended the deadline to June 30, 1982. But that date came and went, and 15 states had still not ratified: Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Nevada, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Utah, and Virginia.

The amendment’s failure to become law was described in the news and by political commentators alternately as a tragedy, a great accomplishment, a disgrace, and a vindication, but most agreed that Schlafly’s vehement campaign against it had played a huge part in its grinding to a halt. Schlafly described the defeat to reporters as a “tremendous victory for women and for families.”

A Legal Conundrum

That was pretty much where things stood until more than three decades later. In 2017, after Trump’s first presidential win, Nevada became the 36th state to ratify the ERA. Illinois followed in 2018; and in January 2020, Virginia became the 38th state. At last the necessary states had ratified, but 38 years on from the extended deadline, could the ERA finally be enshrined into the Constitution?

Under his first presidency, Donald Trump’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) refused to have it added, citing the deadline expiration. Now with a second Trump presidential term days away, dozens of House Democrats have signed a letter addressed to President Joe Biden urging him to convince the country’s archivist—officially, the head of the National Archives and Records Administration—to recognize the ratification and publish the amendment.

“We must continue our efforts to fully affirm and recognize the equality of rights for all people, regardless of sex, as part of our Constitution, a vital effort that has never been more urgent,” the letter states. “This action is essential as we prepare to transition to an administration that has been openly hostile to reproductive freedom, access to health care, and LGBTQIA+ rights,” it adds.

ERA supporters say it’s just a question of publishing the 24 words that they say could change everything. But as many have pointed out, it’s not that easy.

In 2020 Trump’s OLC made the argument that Congress could not short-circuit the amendment process by extending the long-gone deadline. Instead, it said, the whole process would have to start from scratch and it raised further questions over whether five states’ attempts to rescind their original ratifications were valid.

Another central point of contention is whether the time-limit should even have been permitted in the first place. Those calling on Biden to haul it into law before he leaves office say that it should not have. But as Emily Amick, a former counsel to Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, explained in her newsletter: “The ratification deadline is not a historical anachronism—it is something with judicial precedent. I don’t think ERA ratification is the clear-cut legal slam dunk that a lot of us are hoping for.”

Amick also notes that, because congressional ratification deadline is law, it would need to be officially extended in order for the ERA to be ratified. “There is a political argument here to push for ratification, and even to steamroll Biden into doing this to force Trump’s hand-picked Supreme Court to overturn it (under Trump’s watch),” she writes, noting that “this could create a galvanizing moment for further political organizing.” But the problem here, in Amick’s view, is that this “isn’t who Joe Biden is. He isn’t someone who will do something contravening Supreme Court precedent, and I don’t think this is the issue he is going to evolve for.”

For now, it’s back to chants and banners, just like Alice Paul taught us. Will it work in the end? Time will tell. For now at least, the ERA isn’t dead and perhaps that in itself is a victory.