'Disoriented and Not Fully Present'—What to Do When Grief Takes Over

When you're in the fog of grief, you need someone else to make the rules.

Two days after my father's funeral, my mom, sister and I got into a car for the 30-minute drive from Jerusalem to Modiin to look for a new apartment for my mother. We shouldn't have gone. We were in the middle of shiva, the seven days of mourning when Jewish tradition prohibits the bereaved from driving, working, or taking on any responsibilities. But my niece had found a place that seemed promising—affordable and a good location—and we couldn't risk losing it. So off we went.

I will never forget that ride.

Normally, my mom was an excellent driver. Confident, competent, calm, reliable. Not that day. She drove way too fast, then way too slow. The car swayed and swung between lanes. We nearly collided with other cars multiple times. Twice, we ended up in the opposite lane, facing oncoming traffic.

I screamed a few times. So did my sister. My mom sounded completely normal: “Stop worrying, we're fine! I know what I'm doing!” But she wasn't behaving like a normal person. She was driving like someone whose brain and body had stopped communicating with one another. I closed my eyes and started praying—maybe for the first time in my life—and I didn't stop until we got where we were going.

I screamed a few times. So did my sister. My mom sounded completely normal.

That car ride taught me something: When you're in the fog of grief, you need someone else to make the rules—and you need to follow them. In my tradition it’s shiva.

OK, maybe not all the rules—Jewish tradition also requires mourners to sit on low stools for seven days, not wear leather shoes, and keep the mirrors covered. My family didn't follow those because we're not religious. But the prohibition against driving, working, and taking responsibility for anything? That makes a lot of sense. Whoever came up with those rules understood something essential about what grief does to most of us. When we’re in mourning, we’re simply not present enough in body and mind to operate a moving vehicle.

Time and space disrupted

In the days after my father's death, grief dumbed down my senses. I felt dizzy. My vision was occasionally blurry, my hearing spotty. Everything was kind of foggy. My thoughts felt as if they were in slow motion.

Apparently, what I experienced is pretty much universal, according to Jill Greenbaum, a New York-based grief chaplain, whose work focuses on helping bereaved individuals find rituals to carry them through grief—especially when inherited traditions either don't exist or don't fit into their life. “Grieving people consistently describe feeling disoriented and not fully present,” Greenbaum told me. “They may have unusual experiences in the time and space continuum, like time going quickly then very slowly. Their thoughts may feel jumbled and disorganized.”

For me, the disorganization went beyond jumbled thoughts. Sometimes I felt as if I was going crazy.

In the days after my dad unexpectedly died of Covid, my mind would sometimes be completely convinced that he was still alive, while also remembering everything that had happened in the preceding days. Logic had left the building.

The conversation in my head went something like this:

My mind: “Dad is at home right now sitting in front of his computer, or making coffee, or pacing around the room talking to himself about politics and music.”

The last bits of reason: “But if that’s the case, how do you explain being in the cemetery yesterday? Remember, there was a body in the grave? People chanting prayers? The rabbi tore your shirt! What does all this mean?”

My mind shrugs: “I dunno what that was. Something weird. Anyway, we still need to book that hotel for mom and dad—the getaway we got them for their anniversary.”

Reason: “But we’re looking for an apartment for your mom. Not your parents. Only your mom.”

My mind: “We are? That's strange. I wonder which hotel dad would prefer—north or south on the Dead Sea?”

I'd feel totally peaceful and totally fine, and totally convinced that I was being reasonable. And then, something small—a song, a photo, a stray thought—would throw me back into reality full force.

Two losses, four years, one ritual

And now I've experienced this twice. My father died four and a half years ago. My mother died a few months ago. Between those two losses, I learned to appreciate what the Jewish mourning tradition does for those who are coping with loss: When you’re grieving and likely unsafe to yourself, let alone the world around you, you let the ritual guide the decisions.

When my mother died, the only decision to be made was where to hold the funeral. We had to call the local chevra kadisha, the organization that handles Jewish burials in Israel. Then we sent out the death notice. That was it.

From then on, we were in the hands of tradition.

In Jewish tradition, the funeral is supposed to happen within 24 hours of the person passing. The mourner’s clothes are torn at the heart, prayers are recited, and the dead person is buried. Shiva then begins.

My three siblings and I sat shiva in my mother's apartment. We arrived there every morning, like it was our job, unlocked the door and waited for friends and family to show up—no appointment needed.

There was something unexpectedly comforting about the whole setup. The constant flow of people entering without knocking, one after another. People from different parts of our lives—mine and my siblings'—all mixed together, sitting and talking in one room, none of it awkward. We were not expected to entertain. Those people were here for us. They brought food, so we didn't have to think about that either. We showed them our mother's delicate lace work, we pulled out photo albums, we told stories. We also just talked—about our kids, about someone's new dog, about nothing in particular. Shiva isn't all sitting and crying. Mostly you're just... talking, while grief slowly becomes part of the fabric of the everyday.

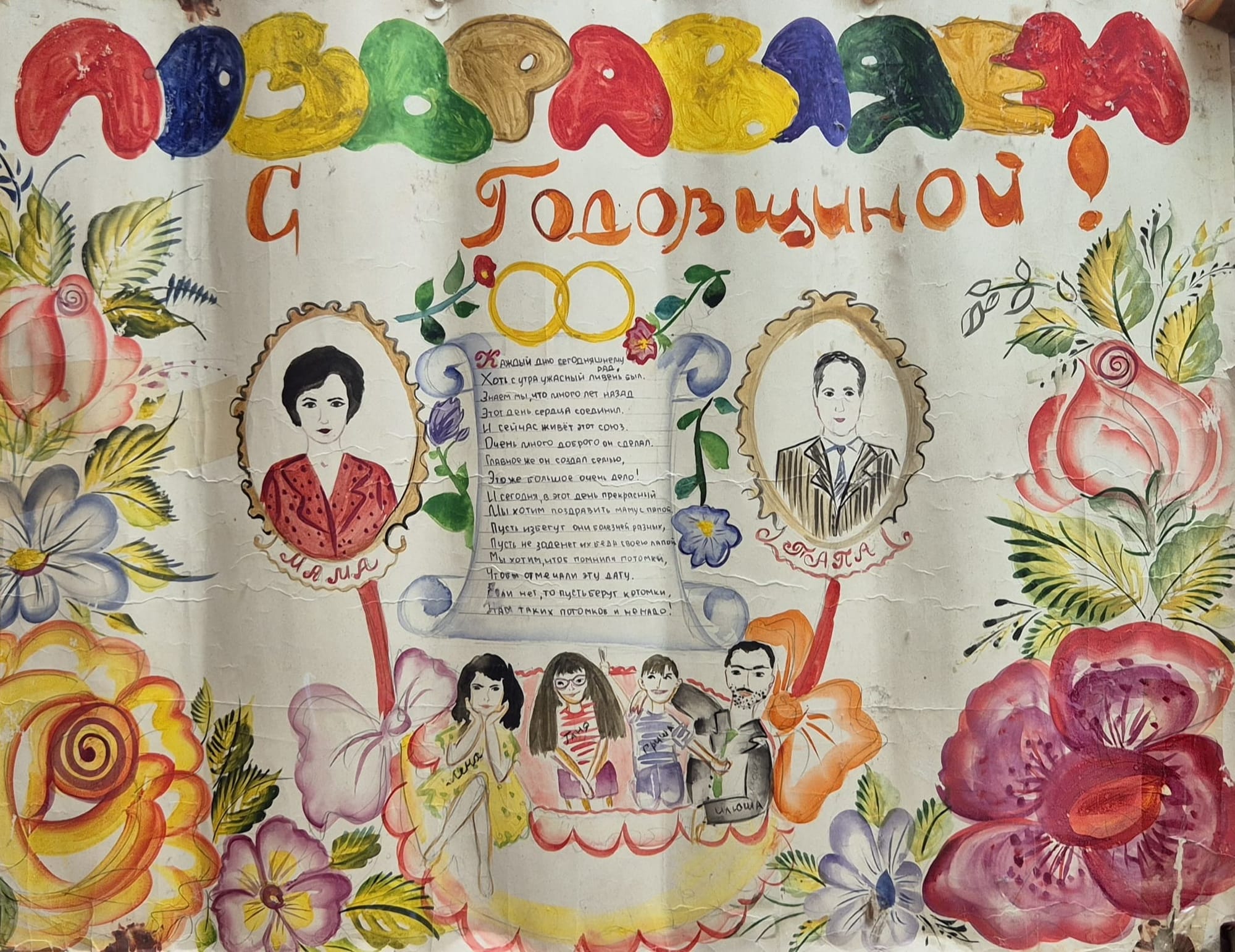

In the breaks between visitors, my siblings and I searched my mom's apartment for treasures. We found a poster we'd made for our parents' anniversary back in 1995 which they'd brought with them from Russia. We found recipes for mom's signature apple crumble and pickle preserves, written in her curly, cursive Russian handwriting.

And then my sister and I found the biggest treasure of all: a round box filled with buttons. When I was little, it lived on my mother’s dresser and I used to spill them onto her bed and play with them. I remember what role each of the buttons played in my imaginary games. I remember the pretty ones, the mischievous ones, the grown ups and the babies, and the two golden princess buttons I called Goldilocks and Goldi-eyes. I played with them while my mom did her mom things in that room: ironed clothes, folded laundry, put her hair in curlers after her shower. I kept some of the buttons and my sister kept some (we had to pretend-fight over this ‘inheritance’ a little bit). Even now, when I take them out, I can hear the soft clink of my mom’s metal hair curlers in the background.

Drifting into small griefs

Shiva gave us permission to do this—to drift into these small griefs, these private discoveries, while the structure of shiva held us safe.

“When we talk about culture,” Greenbaum explained, “there's the culture of the home, there's the culture of the religious community, there's the culture of your ethnicity. But for many people, the rituals they grew up with don't feel like theirs anymore—they've gone down a different path.”

For those without prescribed rituals, Greenbaum encourages experimentation: In grief, try different things and see what resonates, even if that changes day to day. That might be getting out in the fresh air, or staying on the couch. Being alone, losing yourself in a crowd or sharing stories about the person who died. Greenbaum told me that the latter practice—sharing stories and commemorating loved ones, including mentioning their names and celebrating birthdays and death anniversaries—can be more helpful to mourners than therapy.

“Whether we inherit [rituals] or create them ourselves, they are what support us in the process," she says.

For me, in those seven days of shiva, not having to create anything was exactly what I needed. The ritual had already been decided.

I’m not saying it was easy. Shiva provided the structure I needed but it was also extremely exhausting. At the end of each day, my siblings and I, all of us introverts, felt numb from the constant talking. For me, the “socializing” part of sitting shiva was way over the top. It left me so overstimulated that I'd jump at every sound. Sometimes, I felt like if just one more well-meaning person came through the door to console me, I'd drop dead myself.

But maybe that was the whole point—to fill every corner of my psyche so I didn’t have the time or space to withdraw into myself. Shiva, I think, is meant to exhaust you with the sheer relentless presence of other people until all you can do at the end of the day is drop into bed and sleep.

Shiva, I think, is meant to exhaust you with the sheer relentless presence of other people until all you can do at the end of the day is drop into bed and sleep.

And still, the friends and family kept coming—some who I hadn't seen in years. Some came back a second and third time to restock our fridge or load the dishwasher, not waiting for thanks, not even waiting for us to notice. One friend took my daughter to the mall for a couple of hours to give her a break from the apartment and all the strange people filling it.

Mostly, the shiva was about the four of us siblings being together, in the center of it all. We felt hugged by the community and by each other's presence. That apartment, with my siblings—became my safe space.

On the seventh day, the last official day of shiva, we locked the door for the last time and headed to our respective homes. We were now present enough in our mind and body to safely navigate our own paths.

I thought back to that car ride with my mother four years prior, how we shouldn't have gotten in, how I closed my eyes and prayed. This time around, shiva didn't erase the fog of grief, but it did prevent us from getting behind the wheel, allowing us to sink into grief safely—into that box of buttons, those photos, those delirious private dialogues with myself. I could disappear into my mother's dresser drawer for 20 minutes because the structure of shiva held me upright. I wasn't allowed or expected to make decisions. The presence of others kept me tethered to the world even as I drifted.

The ritual underscored something I couldn't have articulated: When you're in the fog of grief, when you're unsafe to yourself, you need to be exhausted into safety. For seven days, we didn't have to figure out what to do with our grief—we just had to unlock the door and let people in.

The real work of grief—the long, solitary part—was just beginning. But I left my mother's apartment carrying something I could use later, for however long I'd need it: the warmth of my siblings beside me, the soft clink of my mother's hair curlers in the background, and the memory of seven days when I felt deeply held.

Tanya Mozias is an essayist who writes The Wrong Globe, a Substack newsletter about language, culture, and living between worlds. Her work has appeared in The Washington Post, Boston Globe, and Oprah Daily. She lives in Israel. 💛 Nataša Jovanić is a Berlin-based illustrator with a background in fine arts, printmaking, and illustration. Her work focuses on the beauty of small moments and everyday life.