Two Years On, The Biden-Harris Effort To Reduce Maternal Mortality Remains—A Start

Maternal mortality is shockingly high in the U.S. What exactly is being done about it?

The Persistent is available as a newsletter. Sign up here to get it delivered to your inbox.

The U.S. presidential election has been, to put it mildly, head-spinning. A CNN debate nobody could stop talking about. An assassination attempt. A late-in-the-race drop-out. A conversation on X plagued by tech troubles. Standing ovations at the DNC. It’s certainly kept us on our toes.

This might explain, in part, why the White House’s sprawling update on efforts to combat the U.S. maternal health crisis—released on July 10—hasn’t been top of mind.

The progress report follows up on 2022’s Blueprint for Addressing the Maternal Health Crisis, a comprehensive endeavor from the Biden Administration, spearheaded by Vice President Kamala Harris, to lower America’s dismal maternal mortality rates. The report was something of a first—56 pages of dense research and policy suggestions, calling on Congress to invest millions.

It couldn’t come a moment too soon.

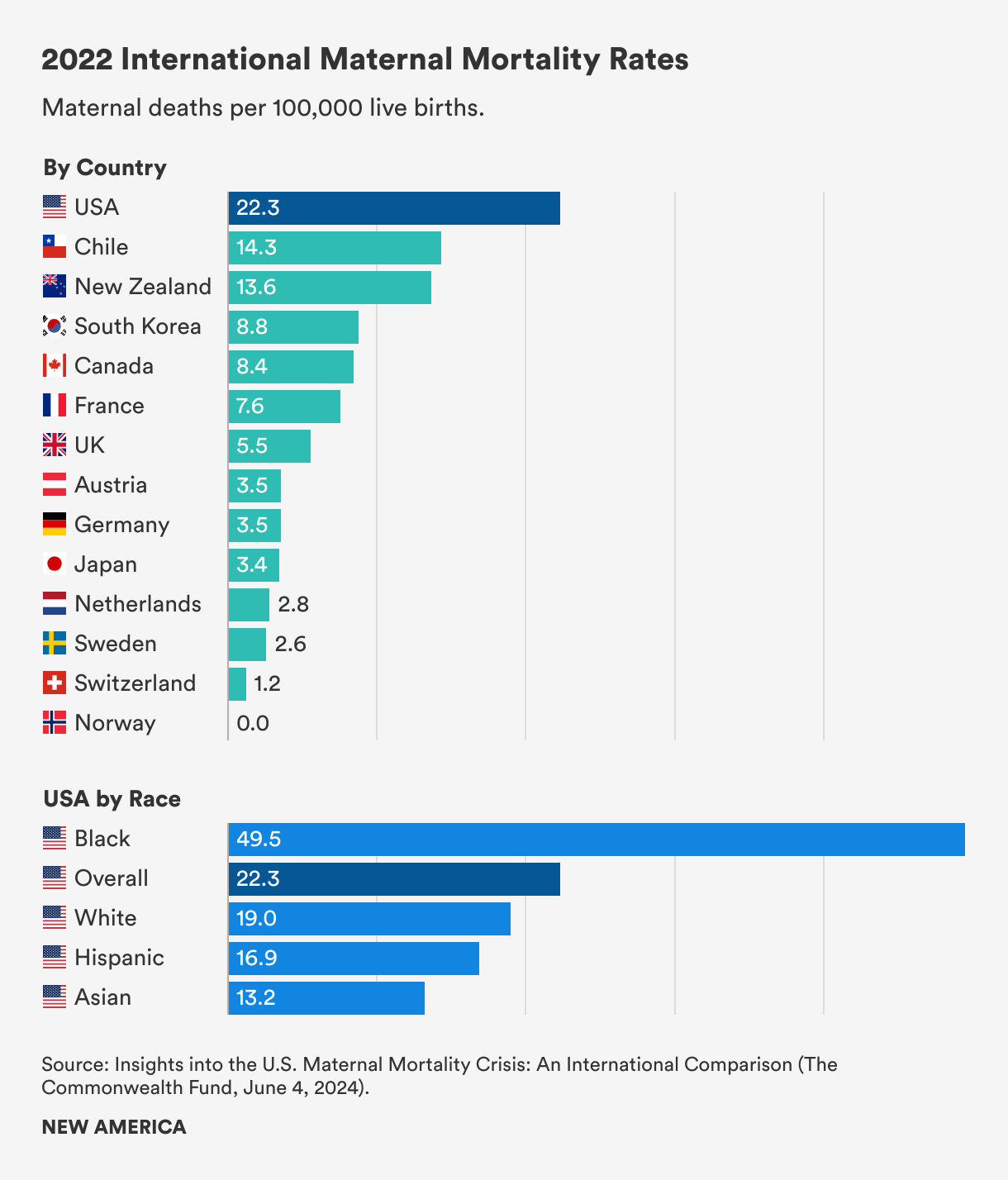

America’s overall maternal mortality rate of 22 deaths per 100,000 live births is fueled, in part, by scarce maternal care providers and a lack of paid family and medical leave. For Black people, who die at a staggering rate in the U.S. of 49.5 for every 100,000 live births, the same issues are compounded by centuries of racism.

Comparing these numbers with those of other high-income countries illustrates how awful they are. New Zealand has a maternal mortality rate of 13.6 per 100,000 live births, and Sweden has a rate of just 2.6 per 100,000 live births, according to data from the Commonwealth Fund, a research foundation.

Unpacking the Blueprint: The Good Parts

In the two years since the Blueprint was released, at least $37 million has been invested in diversifying and growing the perinatal workforce, and more than 37,700 people have called the National Maternal Mental Health Hotline, launched following the Blueprint.

Meanwhile, 46 states and the District of Columbia have instituted a provision within the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 that allows states to expand Medicaid postpartum coverage from 60 days to 12 months. Two states are working on implementing an extension, and Wisconsin has executed limited coverage for up to 90 days.

No doubt, these are important. Expanding Medicaid addresses the 30% of pregnancy-related deaths that occur between day 43 and day 365 postpartum. Nearly 40% of births are covered by Medicaid, a figure that rises to 65% for Black people giving birth. A maternal mental health hotline potentially connects the nearly one in seven women who develop postpartum depression with support. A robust perinatal workforce increases the chance that patients of color and providers share a racial identity—which, research shows, reduces bias and improves patient-provider trust.

Bolstering this is a recent proposal announced by Harris for the first-ever baseline maternal health and safety standards, which will apply to 6,000 hospitals that provide maternal, emergency, and obstetric services. It will ensure these institutions have the equipment and training required for better outcomes for maternal patients.

Unpacking the Blueprint: The Less-Good Parts

Other parts of the Blueprint have missed the mark.

One example that sounds good, but doesn’t measure up in practice, is the Blueprint’s “birthing-friendly” designation for hospitals that have participated in a state or national perinatal quality improvement program and have instituted care interventions, such as supporting breastfeeding and improved health screenings.

It’s a sharp moniker designed to signal to pregnant people that their care will be high quality and safe. But nearly all eligible hospitals have the marker, including Woodhull Medical Center in Brooklyn and Cedars-Sinai in Los Angeles—two medical centers recently in the news for alleged hospital errors that caused the death of a Black woman postpartum. (For the 1,000 acute care hospitals that lack the designation, an analysis by Roll Call found that 800 don’t provide obstetric care.)

A White House official pushed back in a conversation with The Persistent, saying that the designation is only one component of a broader maternal health approach. Plus, the administration aims to get more hospitals into the program. “It is not a gold star saying, ‘You've done your work, good job, you're done,’” the official said. “It is getting [hospitals] into a program where they participate in quality improvement programs, and the requirements for participation, importantly, will be stepped up in the future, and it will become more robust.”

Still, patients looking for a hospital might see the designation as a gold star, even if that isn’t how the administration views it.

While the White House touted its expansion of resources for maternal mortality review committees—which operate at the state and local level and examine deaths that happen during or within a year of pregnancy—there’s no saying these committees actually represent the populations they serve. That’s because there are no across-the-board requirements they need to meet.

In Texas, for example, an anti-abortion doctor was appointed to its state committee in June, and positions for community members were eliminated. This is especially concerning considering that a 2021 report from Black Mamas Matter found MMRCs to be unwelcoming of local communities and distrustful of community insights.

The White House official said the CDC is working with the MMRCs in each state to ensure robust nonclinical representation on the committees and that the voices of people with lived experiences from the populations disproportionately impacted by pregnancy-related mortality in that state are heard.

But this effort is hardly a solution. Intricacies of the Blueprint and progress report contain gaps that require filling—particularly when it comes to helping people on the ground access the care being lauded. The Blueprint levies no calls to universalize family-supportive policies such as ending eviction, universal paid family and medical leave, and univearsal 0-5 child care—even though research supports addressing the social determinants of maternal health in this way.

At the heart of the problem lies America’s deep-rooted racism and sexism, which contributes to poor maternal health outcomes for Black people in particular. The crisis has persisted for centuries and won’t be solved quickly.

Considerable work remains to be done.

Julia Craven is a senior writer and editor with New America’s Better Life Lab, researching Black women’s health and well-being. She’s the brain behind Salt + Yams, an acclaimed newsletter dedicated to Black health history.