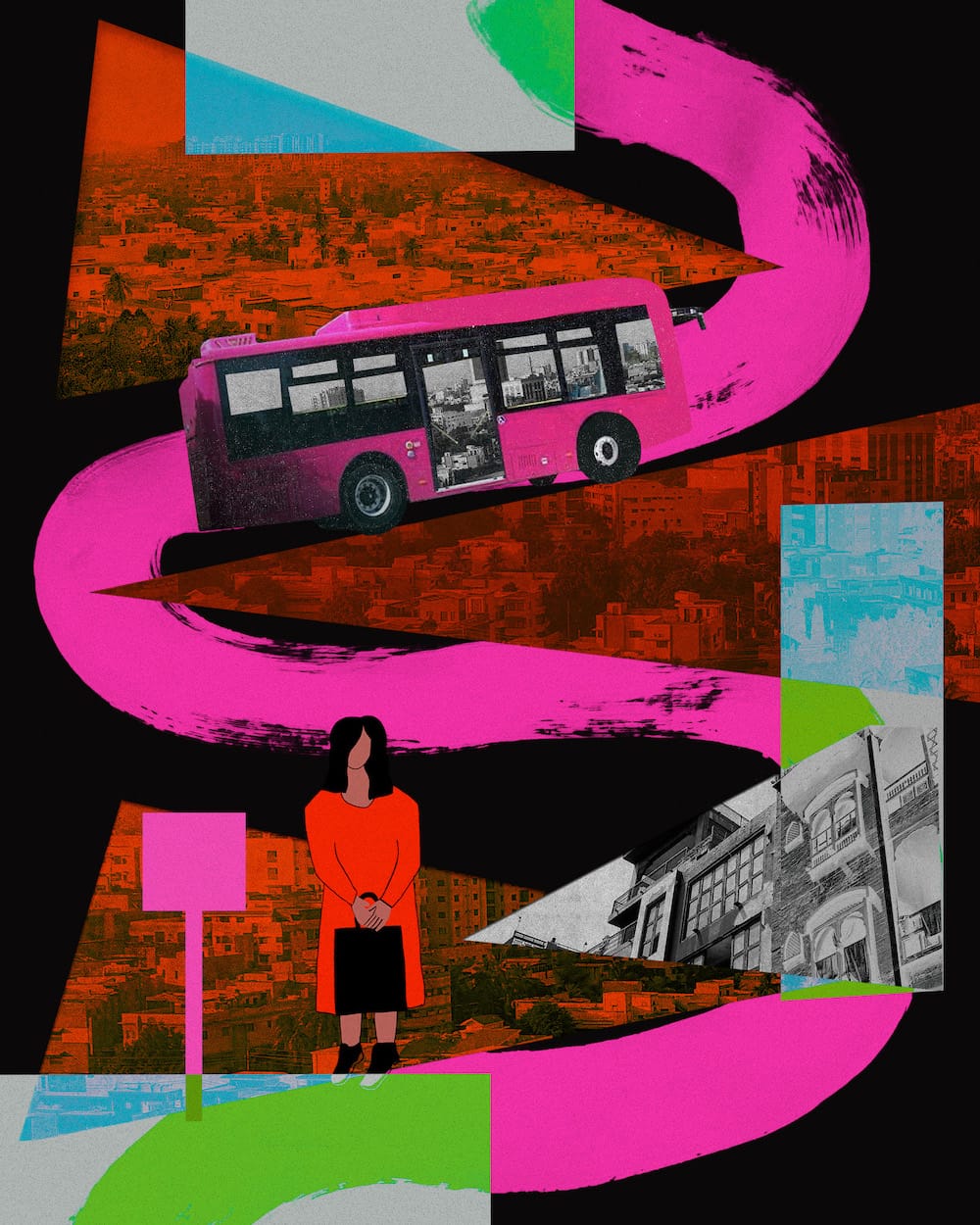

Inside Karachi’s Women-Only Pink Bus

A new women-only bus route is designed to combat the sexual harassment prevalent on Karachi’s public transit system. The bus is clean, spacious—and unreliable.

On a bright Tuesday morning in June, I found myself waiting at the Numaish Chowrangi bus station in downtown Karachi. Crowds thronged past me, racing to catch their buses in and out of the city. More passengers crowded in, weighed down with packages and luggage.

Meanwhile I waited. And waited. And waited.

I was here for route 10—specifically, the “Pink Bus” on that route, a service for women passengers only.

Launched in February 2023, the Pink Bus runs on five of Karachi’s busiest routes. The project, which cost a total of 12 billion Pakistani rupees (roughly $43,000) is government-funded. It started with three routes and 18 buses, each painted a bright, Barbie pink. In April of this year, it added another two routes and 10 more buses.

The service was badly needed. According to a 2014 survey, 85% of working women, 82% of students and 67% of homemakers had felt harassed at least once in the previous year while commuting on Karachi public transport. The perpetrators were found to be fellow passengers (75%), conductors (20%), and sometimes even the bus driver (5%).

Not much has changed. And despite the continued high instances of harassment, reporting it is almost impossible: The only way for women to complain or reach out for help is through social media. And while there have long been women-designated sections on buses, the harassment still happens.

For many women in Karachi, the harassment on public transport is so problematic that they simply don’t travel. That, coupled with Pakistan’s cultural barriers around women interacting with men, is a key factor keeping women out of the country’s workforce. (Just 21% of Pakistan's workers are women.)

The 2014 survey showed that 40% of female students restricted their travel after sunset due to harassment, which reduced their mobility. Cars are prohibitively expensive for most low-income households, and while motorbikes are slightly more affordable, there’s also a much lower social acceptability of women riding motorbikes—although that, too, is slowly being challenged.

Credit for the Pink Bus may go to male politicians like Sharjeel Memon, the minister for transport in Sindh, the province that includes Karachi, but the broader program is run day-to-day by the gender specialist and research analyst Huma Ashar.

Having a woman in this role is important, notes Marium Naveed whose work focuses on urban public spaces and public transportation. “When women are at the table where these decisions are being taken, that's where you really ensure that top to bottom, you’ve thought this through,” she says.

A quick fix is not a solution

Ishrat Jabeen, a gender specialist for Pakistan at the Asian Development Bank, whose work has included projects in the transport sector, notes that without actively tailoring the services to women’s needs—such as having bus routes near schools and creating a safe environment at bus stops, or offering micro-mobility options like women-friendly rickshaws or walking routes to get to and from those bus stops—the Pink Bus could end up being the equivalent of “creating a well without access to water.”

While Jabeen appreciates the initial step in launching the Pink Bus, she points out that all of these factors need to be taken into account for it to really benefit women in the long run.

The reality is that it’s far from perfect. Online information about the bus is scant, and when I ask a traffic policeman, he tells me that sometimes the Pink Bus doesn’t come for three hours. (Officially, it is meant to run from 7 a.m. to 8 p.m.). Also, the drivers are still men. Women have been trained to take up driving the Pink Buses, but the analyst Ashar says they won’t start until 2025.

This isn’t the first time a women-only bus service has run in Pakistan: A similar bus service launched in Lahore in 2012, but lasted only two years before the government pulled funding. Contract violations, such as conductors letting men on board, plagued the project. And it was never commercially viable.

Outside of Pakistan, there have been several women-only transportation projects. The most commonly-cited example is in the UAE, which introduced women-only carriages in the metro in major cities like Dubai, and also operates women-driven pink taxis. Japan and Indonesia are among numerous other countries that have also tested out women-only spaces in trains and taxis; although the scheme in Indonesia was suspended due to low ridership outside of rush hour.

‘They should be able to read the signs’

Back at the Numaish Chowrangi station, a Pink Bus finally pulls into the station after four regular Route 10 services have passed me by.

My wait was an hour. Not bad; could be worse. It’s not particularly surprising since public transport in Karachi is not known for its propensity to run on time.

A woman conductor greets me as I climb aboard, and I easily find a seat—only three others are occupied. The bus is clean, comfortable and emptier than I expected. The air conditioning provides welcome relief from the 35 degree celsius (95 fahrenheit) temperatures outside, and the crowds of men pushing and shoving. I no longer have to watch myself for fear that a man will get too close.

Despite the bus’s shocking pink paint job and signs on the doors and front windows specifying in Urdu that it is women-only, men try to board from the back doors on two separate occasions. The conductor sternly tells them to disembark. Later, when she collects tickets, which are 50 rupees (18 cents each—regardless of distance and the same as the other buses on the People’s Bus Service—about the price of a small chocolate bar), she says guys climbing aboard is a frequent occurrence, and wonders if it’s a prank.

The conductor is convinced that university students—who can read the signs, unlike the 40% of Pakistan’s population who can’t read or write—have tried to clamber on, too. “They should be able to read the signs so I don’t know why they still decide to get on,” she says.

On my ride, a young woman, on her way to university, settles into her seat with headphones in, right behind a mother who is sitting with her toddler, letting him play in the window seat. On the regular red bus, the student tells me, she is navigating crowds of men.

Shafaq, a conductor on route 3 of the Pink Bus, says a big part of her job is helping women who might be new to traveling alone or not used to long travel times. “There are a lot of women going to work or school alone now, who find it easier to do so because of the Pink Bus,” she says.

Critics, who have mainly included prominent feminist academics along with everyday riders, have voiced skepticism about the project, partly because they are wary of segregating women further from mainstream society, and partly because they are worried that, like Lahore’s Pink Bus program, this project might not last long.

Indeed, in Karachi, even proponents of the Pink Bus don’t believe it is a long-term solution to harassment. Jabeen, the gender specialist, notes that separating women can make them less safe as they can quickly become an easier target. But she still believes that by providing a safe space, the bus is serving a purpose.

And if that safe space happens to put women first—while also being clean, cool and comfortable—well, maybe that’s a bus worth waiting for.

Anmol Irfan is a Muslim-Pakistani freelance journalist and editor. Her work focuses on amplifying marginalised narratives within global discourse, with a focus on gender justice, climate and media diversity. She tweets @anmolirfan22.

More from The Persistent.

There's Nothing Small About Microfeminism