When Grief Belongs to All of Us

Could grief over someone I don't know rightfully be mine?

Grief comes to all of us, but I haven’t yet experienced it “properly.” I’m lucky in that respect. I haven’t yet lost my mother or my father or my siblings or my husband; though I have grieved grandparents, who lived long and relatively healthy lives; I have grieved my ability to conceive easily; and I have grieved pets and breakups and occasionally a family friend. In all of those instances, my grief was a private, mostly solitary thing.

But this time last year I experienced a new kind of grief. A terrible thing happened to a person I had only met a few times. Still, for weeks, my grief for that person’s situation stopped me in my tracks: as I ate dinner with my children, as I walked to the store, as I scrolled through my phone in the evening, a wave would crash over me (a cliche, sorry) and I’d be frozen where I was, dazed, blinking the grief out of my eyes.

Because I didn’t know the person well, I didn’t feel it could rightfully be my grief. But even as I berated myself for having the audacity to experience that grief as though it were mine—why was I making it all about me?—I realized that the grief can’t be owned by one person. I felt how I felt. Did that make it wrong? It wasn’t as if I imagined my grief to be anything close to this person’s, but I had to get over the idea that somehow my grieving in this instance wasn’t also mine to feel, that it was somehow selfish.

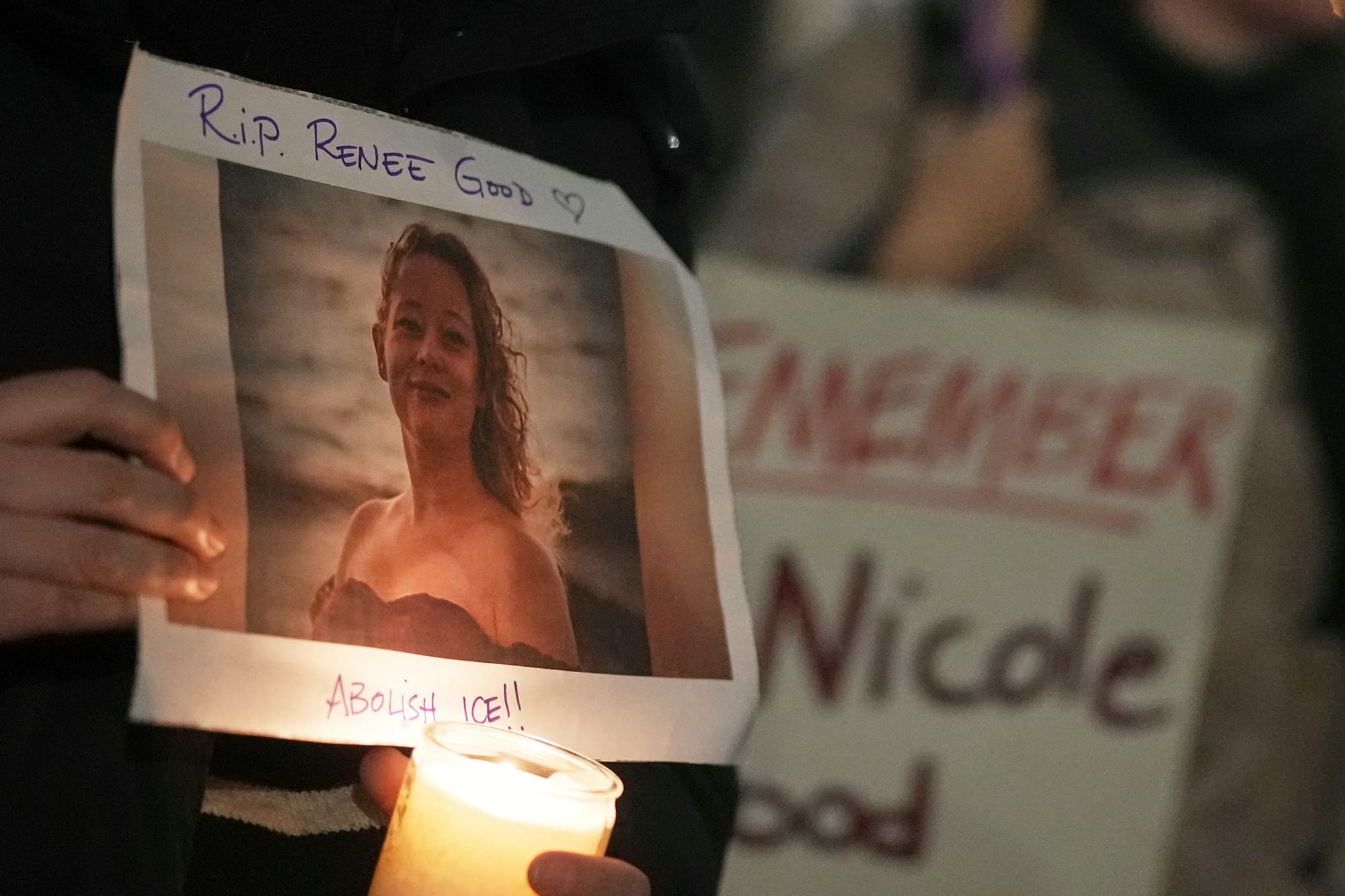

Grieving Good

Last Wednesday, the poet Renee Nicole Good was fatally shot as she peacefully protested the actions of ICE agents in her home town, Minneapolis. It took a moment for the impossible to sink in and then the communal grieving began: A gofundme became so large that it had to be closed with request to “support others in need.” Signs were made, vigils were held, marches were marched. In the aggregate it was many manifestations of grief for a woman most did not know existed until after she was dead.

For the second time I wondered if it was my right to grieve. I am not from Minneapolis, I am not directly connected to Good. I don’t even live in the U.S. Our lives would never in a hundred years have crossed. And yet, I was sad. Was it somehow unsavory that I should mourn her loss as if it was the life of someone I knew?

Meanwhile, the world’s collective grief led to rallies in 1,000 cities over the weekend. It unfolded across social media, where the mayor of Minneapolis has posted images of her standing at a rally, staring grimly ahead, and others have pored over the many videos of Good’s death, offering theories about what it all means. And of course, that grief wasn’t just about Good. It was about a system that they found untenable; about actions they didn’t agree with; about a social contract that felt like it had been violated. It is the right of Americans, after all, to protest peacefully. How had it all gone wrong?

And I thought: the people pouring out their emotions on social media—is it OK that they’re doing this? Are they allowed this grief? Aren’t they making this all about themselves?

Analyzing grief

Last year, as my own, strange kind of grief settled around me I thought a lot about something that had happened in the summer of 2020, a few blocks from where Good was killed. The murder of George Floyd had generated a massive global outpouring of unquestionably real grief. Some 28 million people posted a black square to their social media feeds, an action derided by some as “performative.”

But grieving is performative, I realized. It’s a symbolic way to remember the dead. Once someone’s gone, performance—of rites and rituals, the repeating of memories, performances in themselves—are the only way to remember them. Funerals are all performance.

And in this moment, I realized that it is not constructive to make claims on grief or decide who does or who does not get to grieve. Grief is personal, but it is also public. It is also how we feel. It is processing the unfathomable. Its rites have been performed by every culture for hundreds of thousands of years—335,000 years ago, our small-brained cousins, homo naledi, held funerals. It’s not just us: dolphins, elephants, primates and crows all display signs of grief.

In the U.K., where I live, almost every village and town and city has a war memorial, listing the names of the people who gave their lives in the first and second world wars for posterity. Every year, communities come together for Remembrance Day (the U.K. equivalent of America’s Veterans’ Day), to perform our grief together. We may have forgotten the people to whom those names are attached—but we don’t forget the ritual. Because to forget the ritual would be to fail to mark the grief.

So grief is for us—individually, yes, but also for each other. I don’t think grief is supposed to be a private thing. I think it’s supposed to be a thing we share.

That grief last year was mine; I know what I felt. And though most of us didn’t know Renee Nicole Good, we know her now, and we grieve her loss. And as the weeks and months go by, and our anger at the injustice of her death shifts and settles around us, we should continue to perform that grief, in big and small ways, for as long as we need to perform it. Grief, I think, is supposed to be performed together, and yes, we all get to feel it.