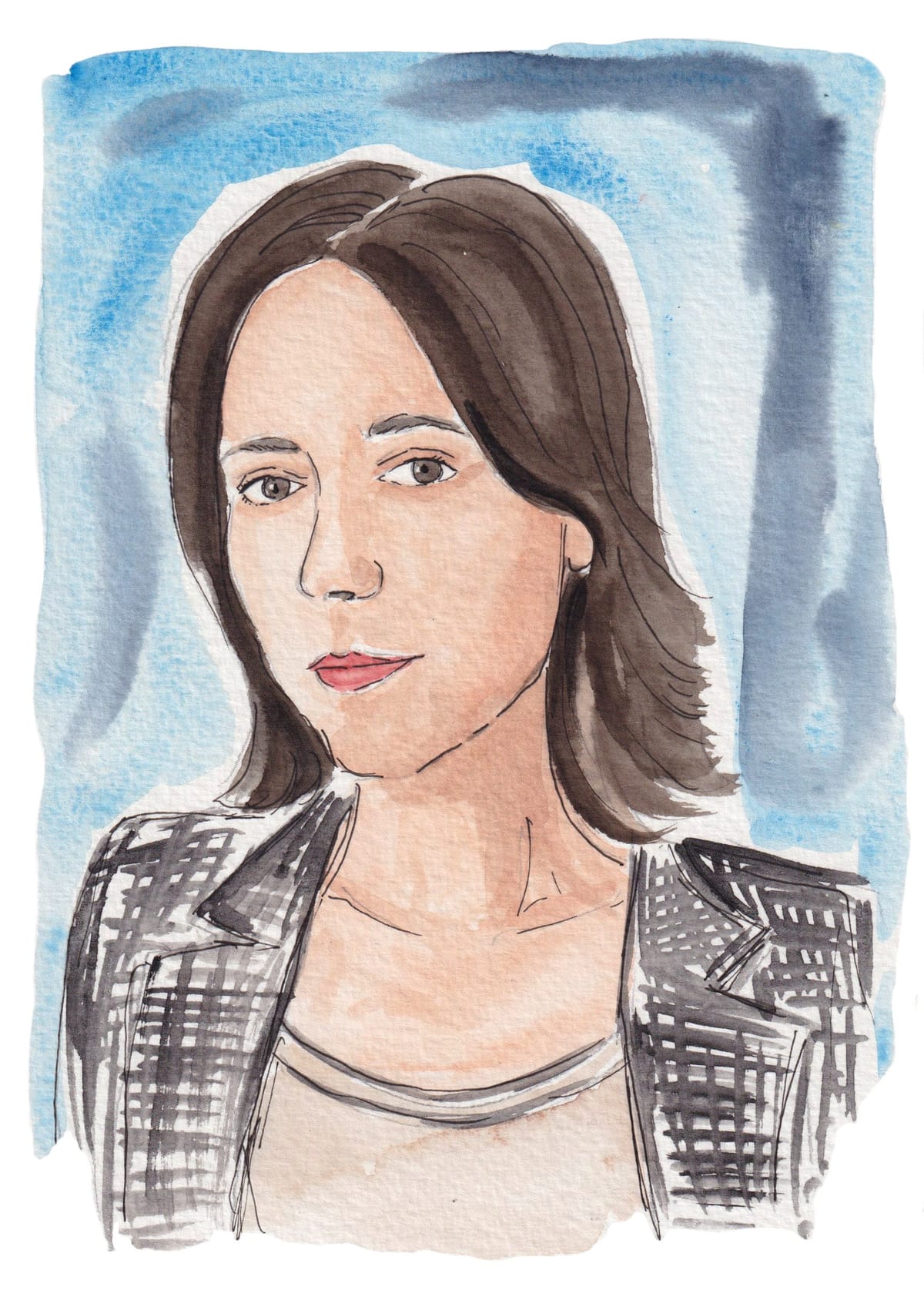

101 Years Ago: The Making of America’s First Woman Governor

She did not frame her success as a triumph of gender or claim to be breaking barriers. Instead, she spoke of civic duty and circumstance

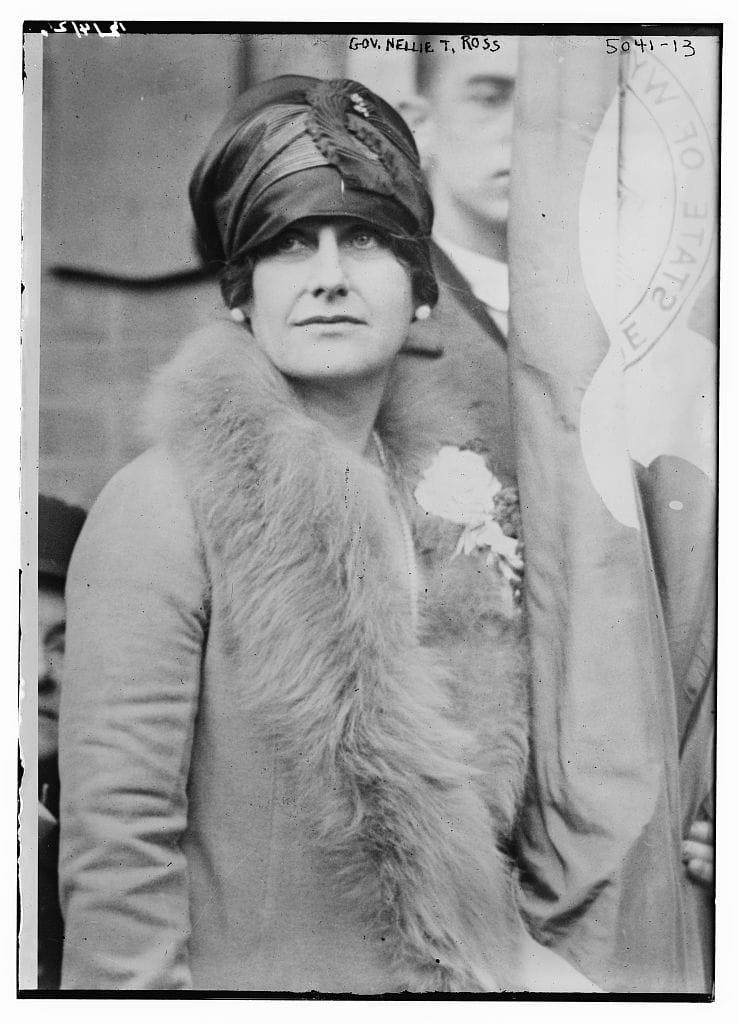

On the afternoon of Oct. 4, 1925, there was a knock at Nellie Tayloe Ross’s door. That knock would not only change her life, it would also chart a new course in American history.

Two days earlier, Nellie Ross’s husband, William Ross, had died unexpectedly at the age of 50 due to complications from appendicitis. He had been the governor of Wyoming—a Democrat in a normally Republican state—and the next election was only weeks away.

When the knock came at the governor’s mansion, Nellie Ross—now a widow left with three sons to raise on her own—was still numb with disbelief and grief, but it was not a friend who had come to offer condolences. Instead, it was the chairman of the state Democratic Committee, bearing an unexpected request: Would she consider replacing her late husband on the ballot?

No doubt the request was the furthest thing from her mind: “As long as my husband lived,” Nellie said, in an interview with The New York Times 15 years later, “it never entered my head, or his, that I would find any vocation outside our home.”

Of course, she ended up doing far more than finding a vocation.

Continuing the work

Nellie Ross did not campaign in the conventional sense. She made no sweeping speeches and promised no radical change. Her candidacy rested on continuity—the assurance that her husband’s work would not be abandoned.

That she kept a low profile didn’t hurt her, either. To voters, her name was already familiar. She had been the governor’s wife, the woman who stood beside him at public events and shared his commitment to progressive reform, like farm subsidies and worker protections.

When the ballots were counted, Nellie had easily won against the Republican nominee Eugene J. Sullivan, and while sympathy undoubtedly played a role in her victory, it was not the only thing that clinched her win. Many voters considered her a continuation of something that had worked: a known quantity at a time of profound uncertainty.

Doing her civic duty

On Jan. 5, 1925—exactly 101 years ago this week—Nellie Tayloe Ross became the first woman in the United States to be elected governor. Although it was a historic moment, Nellie resisted the idea of being held up as a symbol. She did not frame her success as a triumph of gender or claim to be breaking barriers. Instead, she spoke of civic duty and circumstance—as if history had simply arrived at her doorstep uninvited, and she had answered the call because it was the right thing to do.

"Owing to tragic and unprecedented circumstances which surround my induction into office, I have felt it not only unnecessary, but inappropriate for me now to enter into such a discussion of policies as usually constitutes an inaugural address,” she said in her inaugural address. “The occasion does not mark the beginning of a new administration but the resumption of that which was inaugurated in this chamber two years ago.”

That tension between private reluctance and public action would define her life going forward.

A quiet partner

Born Nellie Davis Tayloe in 1876 in St. Joseph, Missouri, the future governor grew up at a time when women’s constitutional suffrage was still a distant prospect and a woman’s place was confined to home and family.

Her upbringing was comfortable but disciplined, shaped by an emphasis on education and moral seriousness. From an early age, she learned to observe more than to assert—a habit that would later define her leadership style.

When she was a child, Nellie’s family moved west, eventually settling in Omaha, Nebraska. The move placed her at the edge of a changing America, where cities were expanding and traditional roles were beginning to shift.

After finishing high school, she attended a teacher-training college and then taught kindergarten for several years before meeting William Bradford Ross, a law student with political ambitions, while on a trip to Tennessee. Their marriage in 1902 shaped her life decisively. Nellie quickly became a partner in his career.

She raised their sons and managed the household, but also assumed the role of professional and public confidante to her husband. Along the way, she developed an astute understanding of policy issues, allowing her to become an important advisor to him while never stepping into the spotlight.

When the family moved to Wyoming, driven by William’s career, Nellie found herself living in a state that prized women’s independence and had long extended political rights to women.

For instance, on Sept. 6, 1870, Louisa Gardner Swain, a 70-year old grandmother, had made history in the then-Wyoming territory by becoming one of the first women to cast a ballot legally, one year after Wyoming’s suffrage act granted this right. A few months before Swain voted, women in Utah had become the first in the nation to cast ballots under an equal suffrage law as part of Salt Lake City's municipal election.

Facing down sexism

During her tenure as governor, which lasted just two years, Nellie worked to preserve progressive policies, supporting aid for struggling farmers, banking reform, and protections for workers and children. The legislature was often resistant to her proposals. It was dominated by Republicans critical of a Democrat in office, and she dealt with constant sexism and prejudice—both explicit and covert—from both those who knew her and those who didn’t. Some newspapers reported that she’d achieved election on the basis of sentiment and that she had no political expertise in her own right. Nevertheless, she governed with steady resolve, determined to fulfill what she saw as her duty. When she lost the subsequent election, she accepted the result without bitterness, returning once more to private life—at least temporarily.

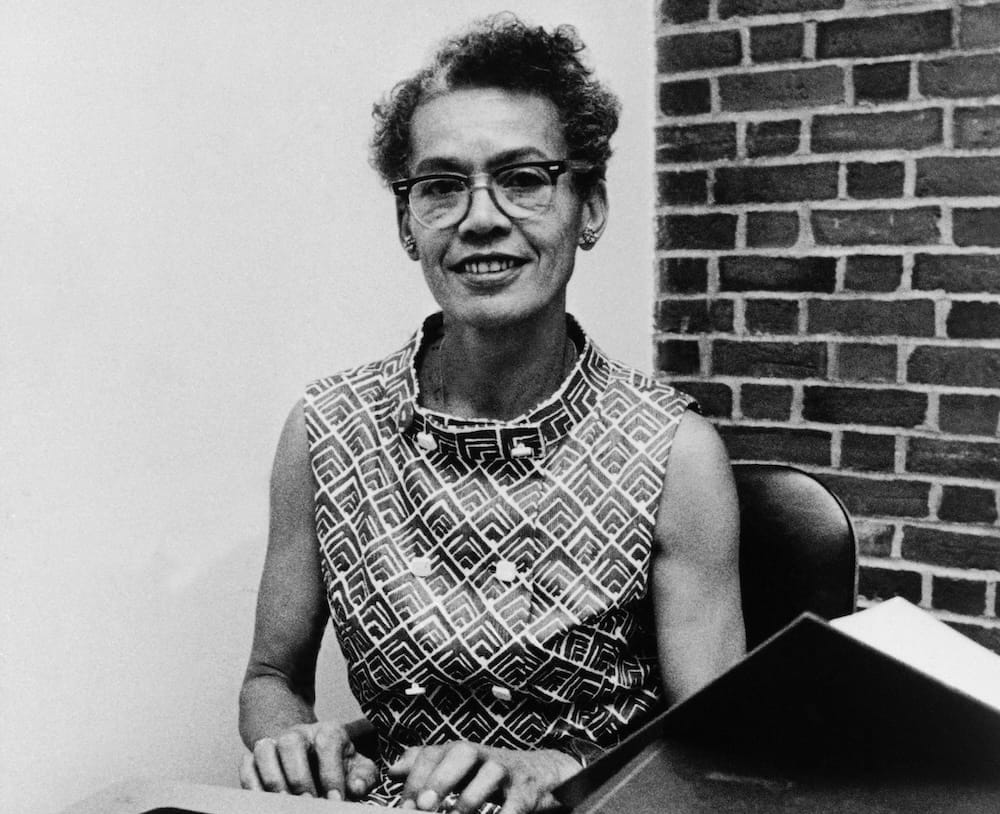

But as it turned out the pull of public life was unexpectedly strong. Nearly a decade later, during the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Nellie director of the United States Mint—the first woman to hold the role.

In 1928, she had become the vice chair of the Democratic National Convention. She moved to Washington, D.C., becoming a leader among democratic women and eventually supporting Roosevelt’s presidential campaign. He saw in her a brilliant political leader and personally selected her for the role.

She ended up overseeing the Mint for 20 years—from 1933 until 1953—ushering it through economic crises, war, and recovery. It was a position that called for patience, precision, and discipline—qualities she’d proved she possessed in abundance.

And though Nellie never sought to be remembered as a pioneer, that is precisely how history should remember her—despite the New York Times obituary blithely describing her gubernatorial term as “unspectacular but efficient.”

Nellie was not only remarkable because she was the first woman to hold a governorship, but because of her style of serving in public office. She showed us that leadership does not always arrive with ambition—but sometimes with a quiet sense of duty in a moment of profound grief.

And indeed, she proved that sometimes history is changed not by those who seek to do so, but by those who step up when they know they must—when they have something to give.