Bread Lines on the Upper West Side and America's Missing Moral Conscience

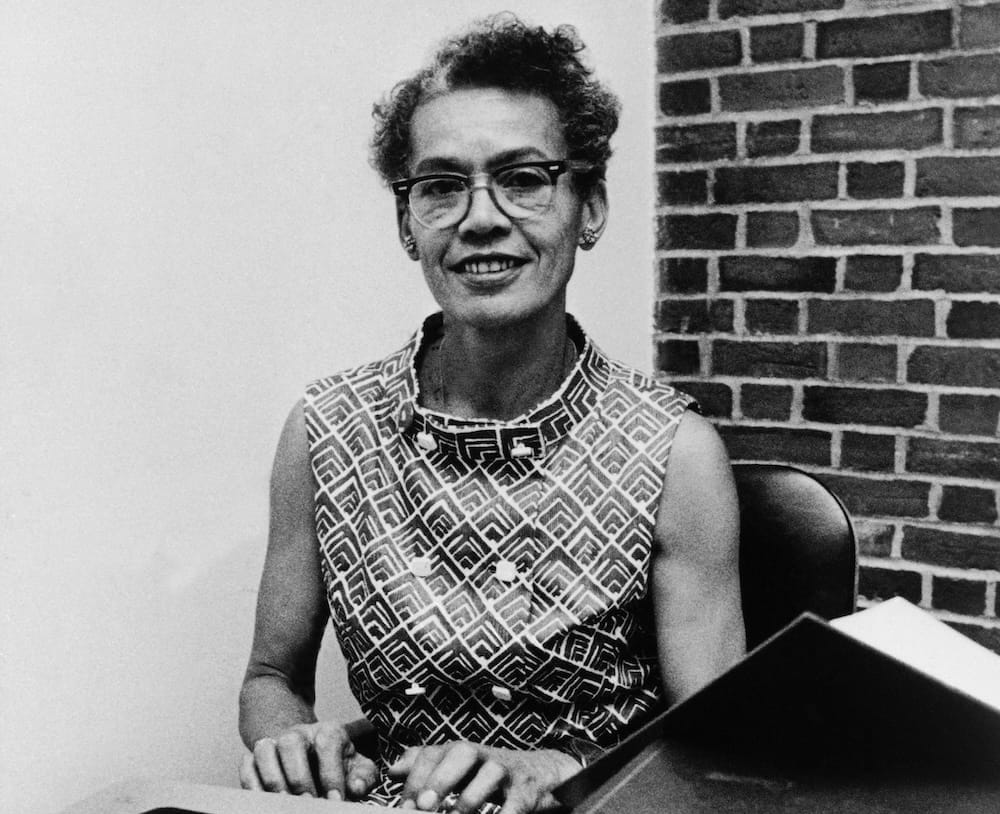

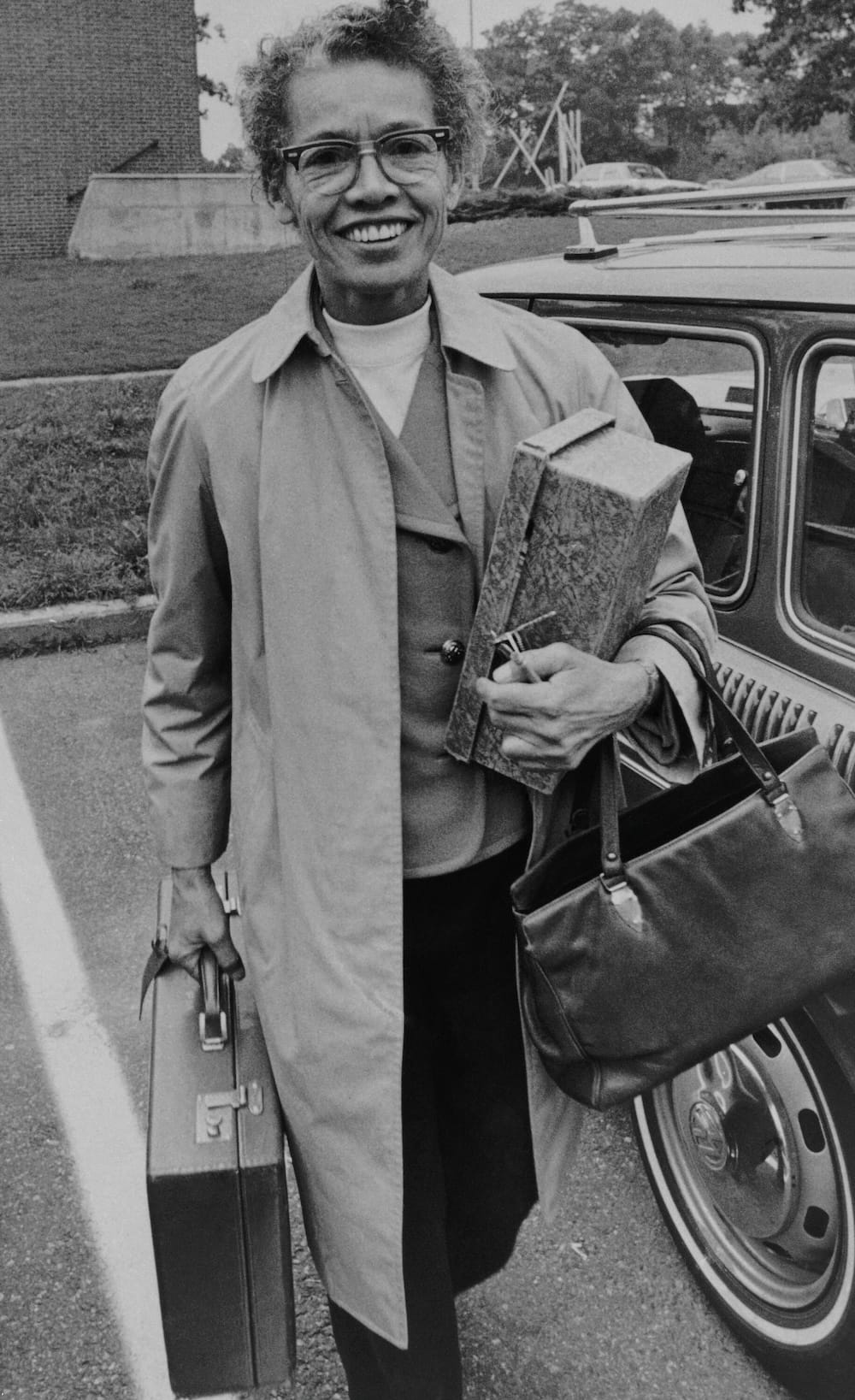

The civil-rights pioneer and feminist visionary Pauli Murray reshaped American law and identity. Her voice matters as inequality deepens.

On Monday morning I walked past a line of people queuing for a food bank on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. It was 8 a.m. in one of the wealthiest neighborhoods in the state, yet the line stretched for five blocks. Older and younger New Yorkers, people of every racial background, stepped quietly into place, waiting for groceries in the chill of a new workday.

This, I found myself thinking, is the start of another week in the so-called land of opportunity—a nation that drew millions to its shores with the promise of streets paved with gold and a meritocratic dream of prosperity. Look at where we are now.

This, I found myself thinking, is the start of another week in the so-called land of opportunity.

The U.S. has, of course, weathered crises before. But in a moment when inequality yawns, institutions buckle, and the narratives that once held Americans together feel threadbare, I’ve been looking to history for steadier ground—and to the people whose moral clarity helped America reorient itself in earlier storms.

For me, one of those people is Pauli Murray. An individual whose legacy is widely felt but largely unacknowledged; hers is exactly the type of voice the current administration lacks. Hers was the moral compass that helped guide Eleanor Roosevelt whose notes to her husband would go on to shape national policy. Indeed, as Americans are standing in line for food, I wonder who is whispering in this president’s ear?

“If she were here today, I believe my aunt would be appalled and saddened, but not shocked,” Rosita Stevens-Holsey, Murray’s niece who I met a few years ago, told me this week. “She would use her skills, education, and experience in a broad approach to help people cope, survive, and act.”

“The issues we are dealing with presently in America, especially in marginalized, immigrant, urban or blue communities,” Stevens-Holsey continued, “would be a call to action for her.”

They should, of course, be a call to action for all of us.

Refusing to Conform

“When historians look back on 20th century America,” the scholar Susan Ware wrote in 2005, “all roads lead to Pauli Murray.” A legal thinker, poet, activist, and priest, Murray shaped both the civil rights movement and second-wave feminism decades before the rest of the country caught up. Yet her slim presence in our history books—if, indeed, she’s mentioned at all—says as much about America as it does about Murray’s brilliance.

Born Anna Pauline Murray in Baltimore in 1910, Murray was the fourth of six children in a family beset by loss. Her mother died when Murray was three, and her father, a Howard-educated teacher, suffered from mental illness exacerbated by physical illness and racist abuse. In 1923, he was beaten to death by a white guard at the Maryland asylum where he had been institutionalized.

After her mother’s death, Murray was sent to Durham, N.C., to live with her aunt and grandparents. Her grandfather, Robert Fitzgerald, a free Black Pennsylvanian who once attended antislavery meetings alongside Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass, loomed as a moral lodestar. Her grandmother, Cornelia, had been born enslaved. Between them, they represented something of a living map for Murray of the nation’s contradictions.

Pauli excelled academically and graduated from high school at 15, but refused to remain in the Jim Crow South. After Columbia University rejected her application because it didn’t admit women, Murray enrolled at Hunter College in New York. Around this time, she adopted the name “Pauli,” reflecting a discomfort with rigid gender categories that would shape her life. Murray preferred boys’ clothing, sometimes went by “Paul,” and later spent years seeking gender-affirming medical care that she was repeatedly denied.

[Editor’s Note: We’re referring to Pauli using the pronouns “she” and “her” in this essay, which matches how she described herself in her writings later in life. It’s also the pronouns that her relatives, including Stevens-Holsey, use today when speaking about her.]

A Mind Against Injustice

The Great Depression of the 1930s limited career options, but Murray, who had by then graduated from Hunter, found work with the Works Progress Administration and began publishing essays and poems in political magazines. Her writing channeled the injustices she had endured firsthand: racial segregation, gender discrimination, economic precarity.

In 1938, she applied to the all-white University of North Carolina for graduate school. UNC rejected her, but that rejection caught the attention of the national press—and, crucially, the eye of Eleanor Roosevelt. The first lady invited Murray to meet her, sparking a correspondence and friendship that lasted until Roosevelt’s death in 1962. Eleanor might have had the ear of the husband, the president. But it was Murray’s wisdom, knowledge and vision that silently guided so much of what was passed on to the most powerful person in the country.

Speaking of Roosevelt in 1982 Murray said: “I learned by watching her in action over a period of three decades that each of us is culture-bound by the era in which we live, and that the greatest challenge to the individual is to try to move to the very boundaries of our historical limitations and to project ourselves toward future centuries. Mrs. Roosevelt … moved far beyond many of her contemporaries.”

Roosevelt, meanwhile, wrote one of the last letters before she died to Murray. “For many years you have been one of my most important models,” she wrote. “One who combines graciousness with moral principle, straightforwardness with kindliness, political shrewdness with idealism, courage with generosity, and most of all an ongoingness which never falters, no matter what the difficulties may be.”

Over and over, Pauli made waves, refusing to sit in the back of a segregated bus (a full 15 years before Rosa Parks would do the same), graduating top of her law class at Howard, coining the term Jane Crow to describe dual discrimination experienced by Black women, writing a book that Thurgood Marshall would go on to describe as the “bible” of the civil rights movement.

Each one of these things individually is a feat. Collectively they add up to a movement. When Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, in 1971, wrote her groundbreaking brief in Reed v. Reed—the first Supreme Court case to strike down a law for discriminating on the basis of sex—she explicitly credited Murray’s scholarship. The Court’s ruling opened the door to countless victories for women and gender minorities. Murray’s fingerprints were all over it, even as history largely omitted her name.

And so it went. Black women were essential to the civil rights movement’s grassroots power, yet rarely invited into national leadership—Murray included. Murray diagnosed these failures long before scholars had a term for them. Decades later, Kimberlé Crenshaw would call it “intersectionality.”

Her impatience pushed her toward action. In 1966, she joined Betty Friedan and others in a Washington hotel room to found the National Organization for Women. Murray co-authored NOW’s founding Statement of Purpose, though her contribution is often erased from mainstream accounts.

The document framed America’s unfinished business bluntly: women were entering the workforce in record numbers, yet still relegated to the lowest-paid jobs; laws, customs, and institutions continued to treat them as dependents rather than citizens.

Throughout her life, Murray kept diaries filled with reflections on identity, race, gender, and the psychic strain of being perpetually misrecognized. “I hate to be fragmented,” she wrote, “into Negro at one time, woman at another, or worker at another.”

As Kathryn Schulz wrote in 2017 in the New Yorker, Murray was “both ahead of her time and behind the scenes.” Her gender fluidity, her refusal to conform politically or personally, and her intellectual range made her impossible to package neatly into the narratives Americans like to tell about progress.

But the effects of her work are everywhere. The legal scaffolding she helped build made it possible for later generations of women and men to challenge discriminatory laws. Her thinking on race and gender foreshadowed some of today’s most powerful frameworks for understanding inequality.

The Lessons We Need Now

Murray died in 1985 at 74. In 2012 the Episcopal Church—she had been ordained as a priest in 1977—named her a saint, describing her as an advocate for “the universal cause of freedom.”

The inequalities Murray spent her life fighting are as entrenched as ever. Black women in America still earn roughly 63 cents for every dollar earned by white men. Data on transgender and gender-nonconforming people show widespread discrimination in employment, housing, healthcare, policing, and everyday life.

Murray herself would recognize the patterns all too well. Indeed, her story offers a compass—a way to see the full landscape of inequality rather than isolated fragments of it.

Murray understood that liberation movements fail when they exclude the very people most harmed by the systems they're attempting to dismantle. She believed that equality had to be enshrined in law and lived in everyday practice. And she modeled a form of patriotism rooted not in myth, but in moral conscience.

As the U.S. grapples with the oh-so-familiar crises of inequality, discrimination and democratic fragility, Murray’s example reminds us what it looks like to insist on a broader, braver definition of freedom. She was the quiet moral conscience that spoke to—sometimes literally whispered to—Eleanor Roosevelt, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Thurgood Marshall and countless others who have more enduring and extensive entries in our history books.

I asked Rosita Stevens-Holsey what specifically she thinks Murray would do if she were here today. “She would lead the way to fight,” she said. The fight, that is, against the “defunding of our public education systems; the weakening library, cultural, and museum institutions; the dismantling of health rights and healthcare systems; the banning of books and the erasure of women's and people of color’s history,” she added.

“With every fiber in her body, she would encourage persistence, faith, and hope—and she would remind everyone that we must not give up or give in.”

“With every fiber in her body, she would encourage persistence, faith, and hope—and she would remind everyone that we must not give up or give in because as Americans we have always struggled for universal justice.”

What I saw on that Monday morning—a line of people waiting quietly for food in one of the richest zip codes in the country—is the kind of American contradiction Murray understood intuitively. She knew that a nation capable of extraordinary progress is also capable of extraordinary neglect. And she believed that the measure of our democracy is how fiercely we fight that neglect.

Murray spent her life insisting that equality is not an abstract ideal but a daily practice—something built case by case, law by law, gesture by gesture, and, crucially, something everyone has a role in shaping.

If we’re to meet this moment of widening inequality and shrinking imagination, it won’t be by clinging to myths about who we once were. It will be by returning to people like Murray who told us, plainly, who we ought to be.

History may have minimized her. That no longer absolves us. Murray left us a map for the road ahead. We dishonor it only if we stop walking.