'Wuthering Heights' is an Awful Book. But the Movie Makes It Better.

I’ve always thought Emily Brontë's classic was a horrible book about horrible people. But Emerald Fennell’s movie, with its moments of tenderness, has made it just a little less horrible.

I’ll be honest: It’s been a while since I read “Wuthering Heights.” It was back in February of 2005, when I studied it for a semester in my last year of high school. As I put the finishing touches on my final essay—probably about tropes of good and evil or something equally obvious—I felt a glorious lightness: the knowledge that I would never have to read it again.

Mine was a battered school copy; it had clearly been through several generations of students, and still had the palimpsests of erased margin notes to prove it. “Why is she doing that?” read one. Who knows what the note-maker was alluding to; probably some weird behavior by the book’s heroine, Cathy. Throwing herself off a crag, or marrying someone she hated, or being cruel to someone. Whatever it was, I feel the note’s author was correct: Nothing Cathy did made any sense.

Here’s my unpopular opinion: “Wuthering Heights” is a bad book.

Here’s my unpopular opinion: “Wuthering Heights” is a bad book. Partly because of its confusing narrative-within-a-narrative-and-then-another-narrative construction, partly for its confusing character naming (everyone’s called Cathy, or Linton, or something beginning with H), but mainly for the fact that everyone in it is despicable, prone to tantrums and meanness and, in one scene I wish I could forget, hanging puppies. You root for no one.

Clearly, my hatred of “Wuthering Heights” was concerning to my dad, because he decided to take me on a field trip to see Top Withens, the farmhouse said to have inspired Emily Brontë. He was determined to help me empathize with Brontë’s characters—or at least to convince me not to hate them. To get there, we drove four hours from our home in Bath to Haworth, in Yorkshire, then hiked for three miles up a steep, rocky path. I wore my white Topshop parka and a pair of thin sneakers, and immediately plunged my left foot into an icy stream.

It was my first trip to the North of England and the landscape was as grim as Brontë described.

It was my first trip to the North of England and the landscape was as grim as Brontë described. As we hiked, the freezing rain turned to sleet. When we reached Top Withens, I realized it wasn’t a house, but the remains of one: In the 10 minutes or so that we examined it, the ice on the squat walls still standing became noticeably thicker as a determined wind blew the sleet directly into our faces.

“You can see why Brontë made Heathcliff a bit wild, can’t you?” mused my dad (who had spent his university days exploring these moors), as he sank a pint of Tetley’s while we tried to dry off next to a crackling fire in the pub by the car park. “Sure,” I said. But I still hated Heathcliff, and his stupid girlfriend, and all their relatives.

After lunch, we tried to visit the Brontë Parsonage Museum, where the Brontës once lived, but it was closed. I squinted up at the sleet-drenched windows and thought about Emily, then surprised myself by feeling a tiny pang of sympathy for her. By the time “Wuthering Heights” was published, she was almost 30, well into what the Victorians would have considered spinsterhood. I imagined her, stuck in this isolated village, staring out over the graveyard of the church where her father was the curate, wondering when her own Heathcliff might arrive.

I imagined her, stuck in this isolated village ... wondering when her own Heathcliff might arrive.

It was with some relief that I discovered that Emerald Fennell’s movie version only tells half the story. The film, which in its opening weekend made an estimated $82 million at the box office, largely from audiences comprising women, ends after Cathy Senior’s death. This is absolutely to its credit, since there can be no confusion about which Cathy is which. (In the second act of the book, Cathy’s daughter, Cathy Jr., survives, and goes on to marry Heathcliff’s son, Linton, giving Heathcliff the opportunity to torture a whole new generation who all have the same names, or at least the same surnames, as their predecessors. And if you’re confused by all this, well congratulations, so is everyone else.)

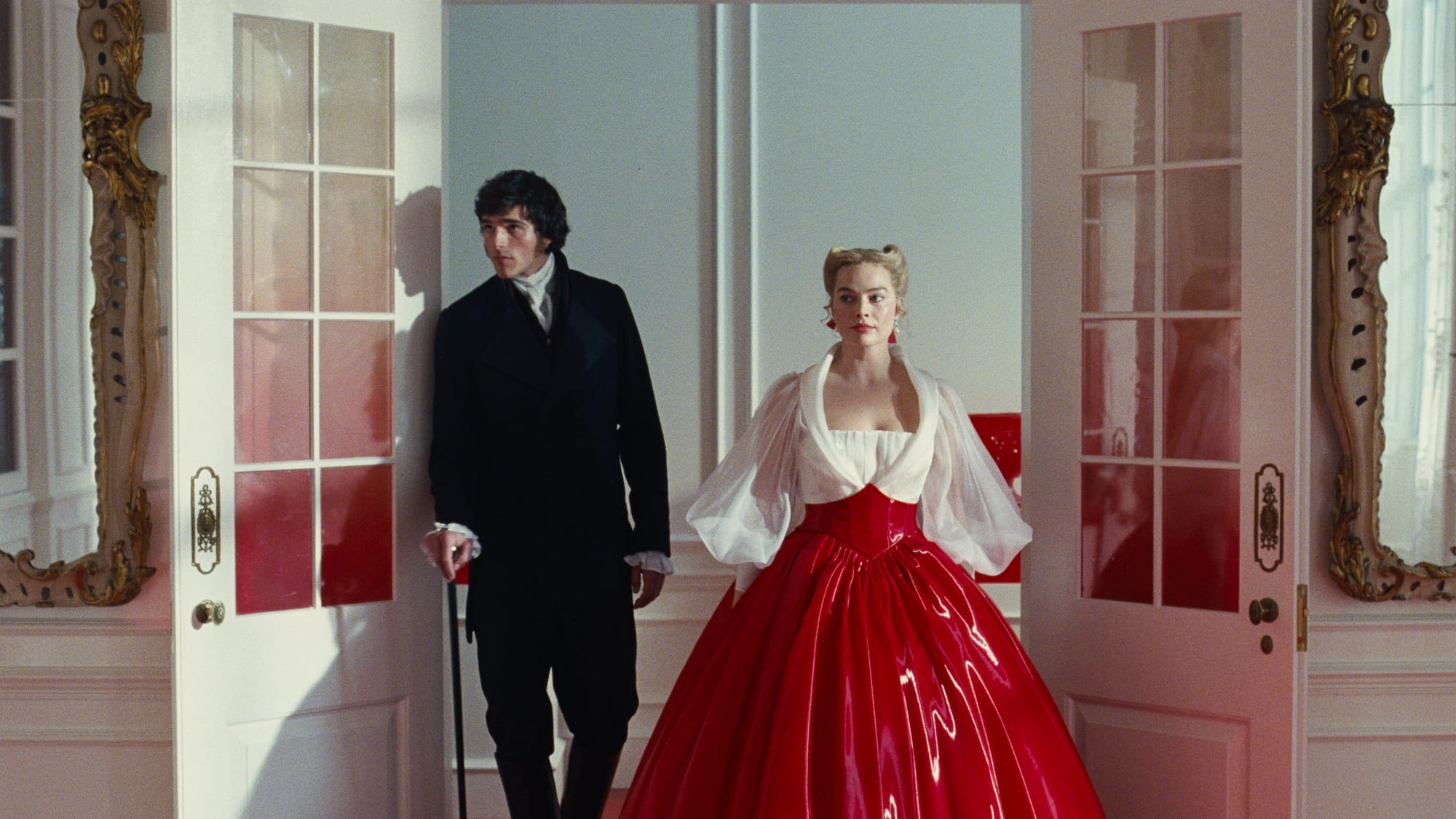

So far, the movie has been criticized for its casting choices (fair—Heathcliff, the male lead and romantic protagonist is one of the few period roles expressly written for a man of color), historically inaccurate set and costumes and extended sex scenes (it having been published in Victorian England, there isn’t much sex in the book).

Watching it, though, I had a revelation: Cathy and Heathcliff and their histrionics are the products of a bored woman’s imagination. With its Gothic setting and its more or less constant rain-soaked tantrums, this storied novel, I realized, is more camp than the tightest pair of riding breeches. And that’s something the director, Fennell, with her melodrama and cream cakes and shiny costumes, completely gets. Case in point: a shocking, arguably deeply misogynistic scene in which Heathcliff humiliates Isabella by forcing her to wear a collar and bark like a dog—the dialogue for which Fennell says was lifted almost “verbatim” from the book—is delivered with Isabella’s squeaky little yaps, dirty yellow ribbons, and a saucy wink.

So yes, it’s true that roughly 75% of the movie consists of close ups of Margot Robbie and Jacob Elordi licking each other, but—I get it now!—that is the point. Surely if Emily Brontë herself could have included scenes of gratuitous shagging during her time, she absolutely would have. “Wuthering Heights” is 1847’s “50 Shades of Grey.” And hey! At least the sex scenes in “Wuthering Heights” provide some moments of tenderness in a story that’s otherwise about cold, bored people dreaming up new ways to torture each other.

My personal epilogue to this tale is that, just 10 months after I put down my beaten-up high school copy of “Wuthering Heights,” I met a boy with baggy jeans and a Yorkshire accent at university. It turned out he had grown up four miles from Top Withens. With apologies for mixing Brontës: Reader, I married him. And I have been forced to spend extended periods among Yorkshire’s crags ever since.

Who knows—maybe there was a small part of me that yearned for Heathcliff all along.