María Corina Machado Won the 2025 Nobel Peace Prize. For That, It’s a Woman We Have to Thank.

Without Bertha von Suttner, an Austrian pacifist, the Nobel Peace Prize might never have come into existence.

The Venezuelan opposition leader María Corina Machado won the Nobel Peace Prize on Friday for her work promoting democratic rights in her country. The Norwegian Nobel Committee praised her "tireless work promoting democratic rights for the people of Venezuela and for her struggle to achieve a just and peaceful transition from dictatorship to democracy."

There have been just 20 female laureates since the Peace Prize started in 1901, but we arguably have a woman to thank for the fact that there’s a Nobel Peace Prize at all. Her name was Bertha von Suttner and she was the first female peace laureate. This is her extraordinary story.

The Merchant and the Mother

The story goes that in 1888, Alfred Nobel had a glimpse of what the future would look like following his death when a newspaper mistakenly published his obituary with the heading “The Merchant of Death is Dead.” Disturbed that this would be his legacy, he decided to establish the Nobel Prizes.

But this story can’t be fully verified and may have been embellished. Scholars think the awakening process was more gradual, and as all good stories go, influenced by a woman that Alfred Nobel once called his “spiritual mother.”

Her name was Bertha von Suttner, an Austrian pacifist, writer, and activist who, in 1889, published her most famous book, “Lay Down Your Arms!” The book’s storyline is from the perspective of a woman who suffered through the Napoleonic wars and lost her loved ones to military violence. It became an international bestseller.

In the 1890s, Bertha became deeply involved in the global peace movement, co-founding the Austrian Peace Society and campaigning for disarmament, arbitration, and education for peace. She attended peace congresses and became a prominent public speaker and writer on peace issues. She would later be known as “the Mother of Peace.”

An intellectual relationship, filled with mutual admiration, that some historians have even called a love story.

But her friendship with Alfred Nobel began long before that. In 1876, she had answered an advertisement for a secretary and housekeeper in Paris. The employer was Alfred Nobel. She traveled to Paris, met him, and stayed for only a few weeks before returning to Vienna, where she married Baron Arthur von Suttner, a nobleman and diplomat who would also be known for his advocacy for peace in Europe.

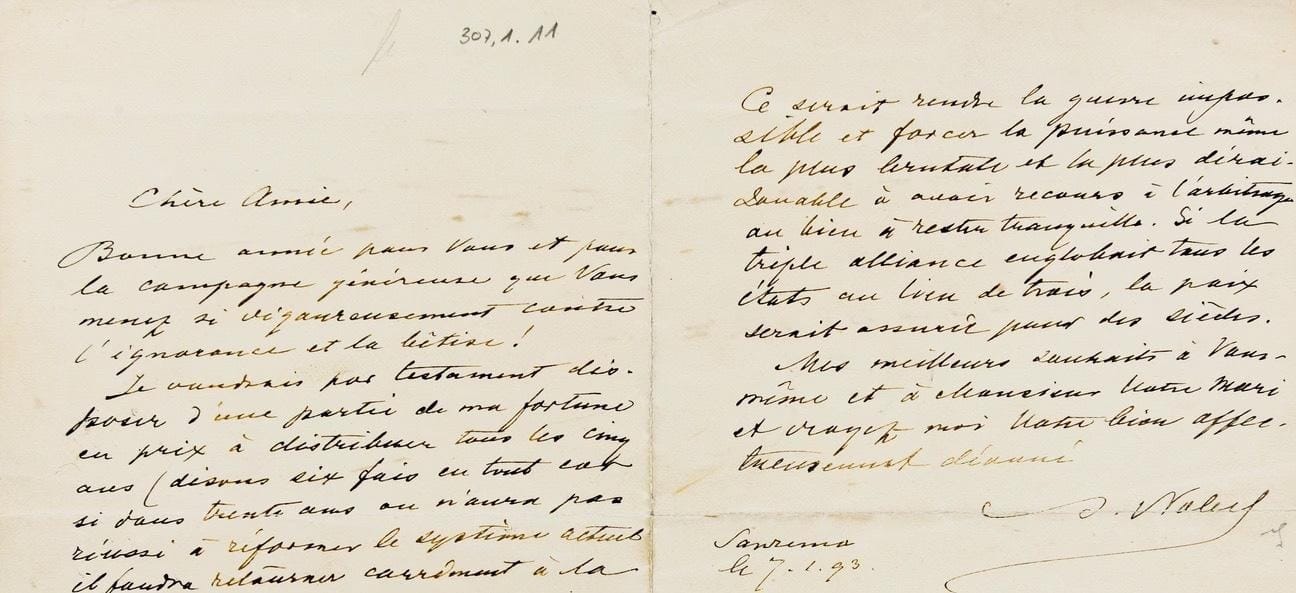

Remarkably, the brief period Alfred and Bertha spent together sparked a decades-long correspondence. They had an immediate intellectual rapport, and while their exchange was not romantic according to scholars, it was occasionally flirtatious and filled with emotional depth that can be described as love. The letters were filled with debates about a wide array of subjects, most importantly, peace and war.

Alfred, known at the time mainly for his inventions in explosives and armaments, was challenged by Bertha’s emerging ideas about pacifism, disarmament, and the moral cost of his technological inventions. She is believed to have had a profound influence on him and his decision to include a Nobel Peace Prize in his will.

We can see Alfred’s conflicted spirit in his letters. He was the man who invented dynamite wrestling with the hope that its destructive power might paradoxically end war.

“Perhaps my factories will put an end to war even sooner than your peace congresses. On the day when two armies will be able to annihilate each other in a second, all civilized nations will recoil with horror and disband their troops.” — Letter to Bertha, 1887.

And we can see Bertha’s unwavering belief in peace as a fundamental right.

“Don’t always call our peace-plan a dream. Progress toward justice is surely not a dream, it is the law of civilization.” —Letter to Alfred, 1893.

Their friendship came full circle. It began as a short-lived secretary / housekeeper job, but blossomed into an intellectual alliance that has an eternal stamp on history. Bertha inspired Nobel’s testament, and he elevated her life’s work. With his doubt and her conviction, his resources and her vision, together they built a bridge with great affection. In his final letter to Bertha, shortly before his death, Alfred wrote:

“I, who don’t have a heart, metaphorically speaking, I do have such an organ, and I feel it…heartily yours”— Letter to Bertha, 1896.

He had praised her work over the years and had already written into his will the annual prizes to those who conferred the “greatest benefit to humankind,” including:

“…the most or best to advance fellowship among nations, the abolition or reduction of standing armies, and the establishment and promotion of peace congresses” — Alfred Nobel’s will, 1895.

Women, Men, and the Nobel Peace Prize

In 1905, Bertha von Suttner became the first woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize, nine years after Alfred Nobel’s death. In the first half of the 20th century, only three women were awarded the prize. That number rose between 1976 and 2023 to 16 women. In 2011, three women shared the prize.

The early history of the Nobel Peace Prize reflects how peace was defined narrowly by male diplomats and heads of states brokering ceasefires. Women, who were disproportionately affected by wars and organized grassroots resistance, were excluded from formal peace negotiations. It wasn’t until the 1970s and 1980s that women who led grassroots, civil society, and nonviolent movements began to gain recognition.

During this time, all female laureates were from Europe or North America, demonstrating Eurocentrism or Western-centrism. Only from 1991 onward did women from other regions begin to appear among the laureates, reflecting a broader awareness about women’s leadership and that peace is about dismantling oppression, poverty, and colonial legacies.

And when women were recognized, it was almost always for unpaid, informal, under-resourced work, while male laureates often received recognition for holding high-level positions, sometimes even as leaders of the very governments that waged the wars.

The double standard has meant that men have been awarded for exercising formal authority, even if that authority perpetuated the conflict. Women are often awarded for struggling outside those systems, without institutional power, and often at great personal risk, with far fewer resources.

It’s important to note that the Nobel Prizes come with a significant financial reward. In 2025, the amount is 11 million Swedish kronor, which is approximately $1.17 million in current exchange rates.

It matters how we got here. Alfred Nobel listened to Bertha von Suttner and integrated her work into his. More than 100 years on, it still matters very much.