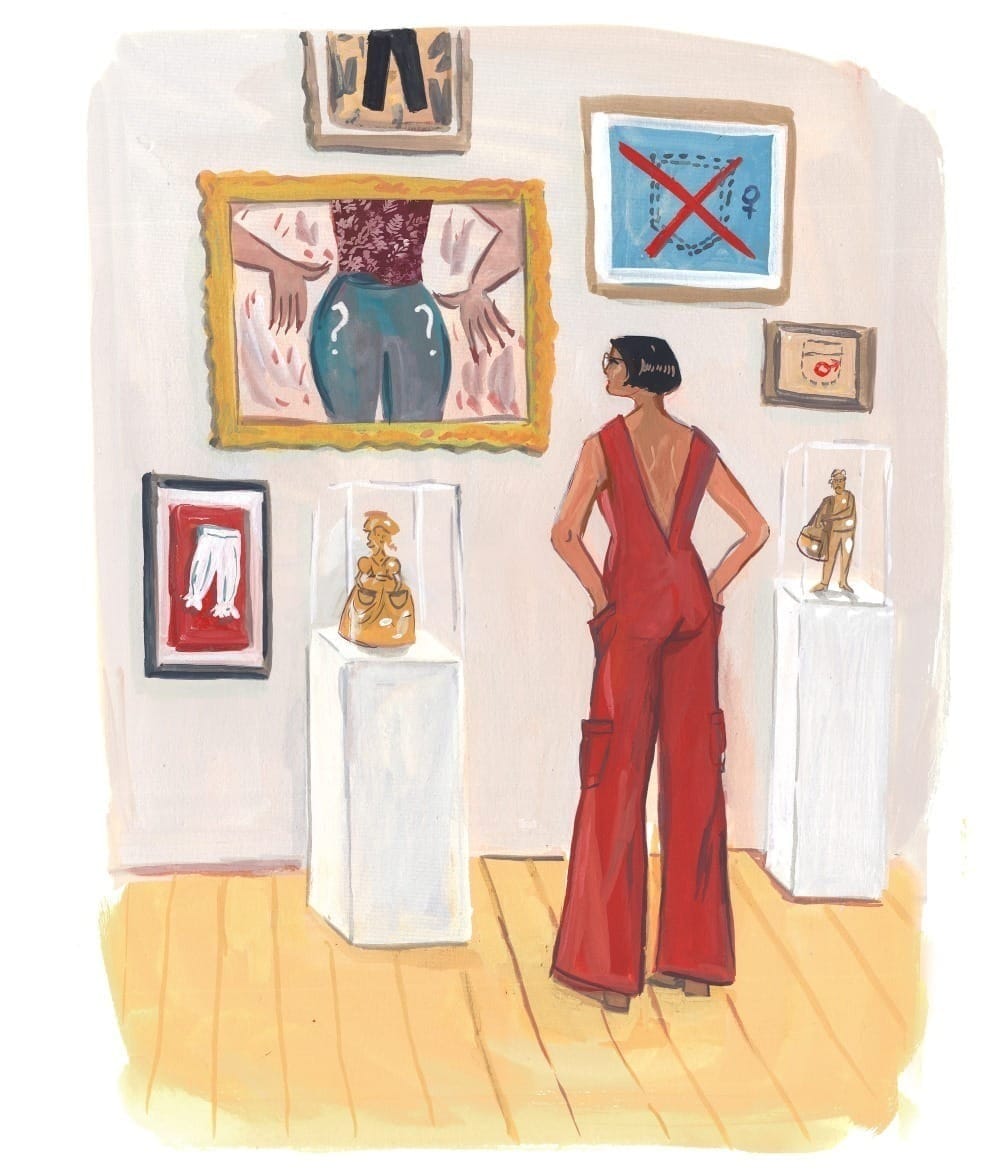

Why Are American Women Still Taking Their Husband's Name?

What’s in a name? For women, maybe everything. An exploration of the never-ending battle over women’s surnames.

I have a name so commonplace (Kathleen Davis) that if you Google it, you’ll find me among authors, actors, non-profit employees and dozens others with the same name.

I once almost couldn’t renew my driver’s licence in New York because there was another Kathleen Davis with my exact first, middle and last name, birth date and height. Truly, my name doesn’t make me unique.

But still, I’ve known since the time I was a child that I’d never change my name if I got married. To me, my name is a fundamental part of who I am, something that shouldn’t have to change just because my relationship status does.

What’s in a name?

The tradition of a woman changing her last name from her father’s to her husband’s is part of an English law called coverture, and it came to the U.S. with English immigrants in the 1600s.

The logic of the law went something like this: A girl does not have a legal identity when she is born, and belongs to her father until she marries, at which point she assumes the legal identity of her husband. Thus, the logic went, she should carry her father’s name until she is handed off to her husband and carry his name.

In the eyes of couverture, women were the property of their fathers—and later their husbands—along with his land, house, farm animals and any children she had. Under coverture, not only could a woman not vote; she was also not allowed to own anything, make a contract, have custody over her children. She was not protected from physical abuse including rape by her husband.

Couverture laws may have slowly been dismantled over time, but the tradition remains in the form of women today still changing their name upon marriage.

My decision to keep my last name wasn’t a conscious middle finger to that ugly history, but like most women, I don’t view myself as my husband’s property any more than he views himself as mine. Why should I change a name I’d carried my whole life, a name I built a professional identity around, just because I’m a woman?

In general, keeping my name and giving my kids hyphenated last names hasn’t caused any issues, However, I have encountered resistance from his family who see my decision as bucking the natural order of things. Thirteen years after our wedding, relatives still address our mail to Mr. and Mrs. Beazley.

To keep or not to keep

Keeping my last name after my marriage in 2012 hardly felt revolutionary, but in America at least, my decision was rare. Nearly 80% of married women in opposite-sex relationships said they took their husband’s last name according to a 2023 Pew Survey.

And I felt like I was following in fine footsteps: In 1855, Lucy Stone, a 19th-century suffragist, was the first documented woman in the U.S. to keep her maiden name after marrying.

Lucy Stone’s stand inspired other women to do the same, eventually prompting the creation of The Lucy Stone League in 1921, which fought for women to have the legal and social right to use their own names for all aspects of life.

But just as it’s important to me and to Lucy Stone that we keep our birth names, the ability to change your name can be equally as important.

For transgender and non-binary people, the ability to change their name to something that aligns with their identity is fundamental. For that reason, laws that forbid people from changing their name can be even more harmful.

A (very) slow road to progress

It took the U.S. over 200 years to get rid of coverture laws. In 1839, Mississippi became the first state to pass the Married Women's Property Act, which established that married women could be recognized as owners of their own property. New York followed in 1848 with a more comprehensive act that also allowed women to keep their own wages. (Though New York became a model for other states, it took until 1900 for the act to pass nationally.) But elements of coverture law persisted into the 1960s and 1970s—with single or divorced women unable to get credit in their own name.

Then, in 1972, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that the automatic changing of a woman's name was merely a custom, not a legally binding aspect of law, and finally marital rape wasn’t recognized nationally as a crime until 1993.

With the second wave feminist movement in the 1970s and the changing of some laws, the idea of women keeping their own last name gained popularity; it slowly climbed from there to around 20% in the 1990s where it has remained for 30 years.

Meanwhile, some women began changing their maiden names to something else entirely, reasoning that their surname wasn’t really “theirs” anyway, since that had been handed down by the father.

And therein lies one of the key arguments against a woman keeping her last name: that if we choose to keep our given name, we’re still carrying on the patriarchal line since chances are our last names came from our fathers.

Feminists have grappled with this question, as well as with the desire to share the same last name with their children. In the U.S. more than 96% of children have their father’s last name only, regardless of whether their parents were married or the father was even involved in their lives.

Name changing throughout the world

While women taking their husband’s last names is still popular among heterosexual couples in the U.S. and the U.K., (about 90% of British women take their husband’s name when they marry), in the last few decades, some countries around the world have changed laws around married surnames. Norms have also evolved.

Several countries including France, Greece and Italy have laws that either don’t permit people to change their birth name or make it extremely difficult to do so. In Quebec, a law passed in 1981 forbids a woman from taking her husband’s surname after marriage. The rule was put in place as part of the 1976 Quebec Charter of Rights’ statement on gender equality. The law in Greece, requiring all women to keep their maiden names, was also a result of a wave of feminist legislation in 1983.

The Italian government makes it so difficult to change your last name that it's rarely done. Changing a surname requires an application with “compelling documentation and significant reasons.” (Coincidentally, Italy has one of the lowest marriage rates in the world.)

In France, the social and legal norm of women keeping their name at marriage goes back to a 1789 law requiring that people not use a name besides the one given on their birth certificate. In China, Vietnam, Korea, Ethiopia, and Senegal women keeping their last name after marriage isn’t a law, it’s a cultural norm.

But then there’s Japan, which stands out as the only country in the world with an explicit law dictating that married couples must share the same last name. A full 95% of the time it’s the wife who takes the husband’s last name, not the other way around, (though it can be done).

Japan’s first female Prime Minister, Sanae Takaichi, a staunch conservative, is a vocal supporter of the law, despite the fact that she’s kept her own last name. During her first marriage, she assumed her husband's last name legally, but continued to use her maiden name in public life. When she divorced she reverted back to her maiden name, and upon remarriage to her ex-husband he took her last name in order to fulfill the legal requirement.

For a woman who has herself bucked tradition and held onto her professional identity, it’s surprising that she’s so adamant about preserving an outdated law and insisting on “traditional” family structures.

The personal is political

With all that’s going on in the world, worrying about names may seem inconsequential. But language is symbolic and significant. How we name things is a signal to the world of identity and agency. Your name is the first thing that tells the world who you are.

Views on marriage have evolved since the days of coverture, and it’s time our views on last names shift, too.

When I decided to hyphenate my children’s last names, a lot of people said, “what are they going to do when they get married?” My response: “If they get married, they can choose to do whatever they want.” If they decide to drop half of their hyphenated last name, or to form a whole new name with their partner, or to give their children three hyphenated last names, it’s up to them.

Equality thrives where there is choice.